In his classic 1965 book, Nirad Chaudhuri called India “The Continent of Circe.” (In Greek mythology, Circe seduces Odysseus and his men with her songs, turning them into swine.). Sixty years later, South Asia – which in its historical sense includes the countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan – continues to suffer from the conundrum that Chaudhuri identified.

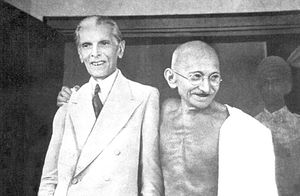

South Asia makes up about a fourth of the world’s total population. It was an economic powerhouse through most of world history, contributing about 30 percent of the world’s GDP before colonization – though by the end of colonization, its GDP share had shrunk to just 2 percent. The region has also produced political giants like Mahatma Gandhi, Quaid-i-Azam M.A. Jinnah, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. With its vast pools of talent and economic potential, the region could have become one of the world’s major political and economic engines – an Asian version of the European Union. However, because of its internal contradictions, fed by communal animosity, it has fallen short.

Unlike Europe or Southeast Asia, South Asia has not seen much regional cooperation over the years, whether on economic growth, human development, or other causes of global good, including climate change mitigation. Instead, its two largest nations, India and Pakistan, have fought three wars and been involved in several major military skirmishes. The last major skirmish, fought in May 2025, was particularly frightening due to the real threat of nuclear weapons being used.

The latest clashes led to a rise in jingoism in India and Pakistan, with the governments, media, and even public intellectuals in both countries each claiming “victory” over the other. In reality, both countries have lost. The skirmish could easily have descended into a full-scale war, putting the lives of thousands of people in South Asia at risk. Urgent steps need to be taken to mitigate the risk of further military clashes, if the constant threat of war in the region is to be fully averted.

The Role of the Public Thinker

It is no secret that India-Pakistan relations are today at their lowest ebb. The two governments are not talking to each other. Trade has virtually ground to a halt. Following the incidents of the past few months, bilateral trust has frayed considerably. Quite unprecedentedly, even relations between the Indian and Pakistani cricket teams, whose famed camaraderie has historically withstood political frictions, are today strained.

In such circumstances, the role of the public thinker – the scholar, the commentator, the artist – becomes particularly important. Rather than emphasizing the differences between the two countries, scholars, commentators, and artists have the responsibility to foster peace by emphasizing the region’s vast historical and cultural common ground. This is one way to ensure that the people-to-people connections between the two countries, which are being strained by the governments, do not completely fall apart.

Public thinkers can place greater emphasis on the Subcontinent’s shared past, including historical figures that transcend national identities, in their work. These historical figures include Tagore, Asoka, Akbar, Guru Nanak Devji, and Dara Shikoh, as well as Sufi and Bhakti poets who have emphasized coexistence, such as Bulleh Shah, Kabir, and Amir Khusrow. This could help to build bridges among the peoples of the region.

Public intellectuals can also emphasize aspects of South Asian culture that could foster greater understanding and evoke mutual respect, such as the Hindu concepts of shanti or peace and ahimsa or nonviolence, the Hindu and Sikh concept of seva or service, and the overlapping Islamic concept of sulh-i-kul or peace with all. Films, documentaries and plays (such as “The Trial of Dara Shikoh” and “Gandhi and Jinnah Return Home,” which I wrote and which have been performed several times), as well as popular music, can play a vital role in highlighting these commonalities.

It would also help to recall the unifying sentiments of the founding fathers of India and Pakistan in popular culture and media. For example, not many Indians know that the Mahatma had wanted to spend three months of every year in Pakistan, that he began his prayers with readings from the Quran, or that he prevented the slaughter of Muslims by undertaking a fast unto death.

Similarly, Jinnah, who had declared himself the “Protector-General” of the Hindu minority, had generously included educational institutions in India, including in Bombay, Aligarh, and Delhi, in his will. In his famous first speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, Jinnah declared that all religious minorities were free to go to their houses of worship and that they had full rights as the citizens of the new nation.

The Next Steps by South Asia’s Leadership

Pakistan’s rebuilding of the Sikh Gurdwara at Kartarpur and giving Sikhs, particularly from India, open visa facilities facilitated religious visits and created great goodwill. The countries of South Asia, while hosting diverse populations, have a connected religious and cultural heritage. Hence, similar creative steps should be taken by the countries of South Asia to promote greater people-to-people movement across the countries, particularly on the basis of religious pilgrimages and cultural tourism. Such steps help remind people of the various South Asian nations of their commonalities and will help foster religious harmony.

In time the countries of the region, while remaining independent, should aim to create economic zones and alliances for regional growth and prosperity keeping in mind the example of Europe, as Southeast Asia has done with ASEAN.

The time has come to move beyond platitudes and empty goodwill gestures and think of concrete, long-term suggestions to promote harmony and peace. Greater cooperation among South Asian nations will increase regional growth and prosperity, enhance regional security, and most importantly, improve the prospects of peace.

Positive steps toward building bridges across cultural, and religious divides will be negated in the current heated and often venomous atmosphere promoted by the media. Leading figures in the media need to understand their responsibility and play their role in bringing down the temperature in the larger cause of promoting peace. Without this effort, the media will continue to generate hatred against the other and attempts at peace will be frustrated.

Perhaps Chaudhuri’s metaphor could then be put to rest. Together, Gandhi and Jinnah can overcome Circe.

This essay was first published in the Asian Peace Programme (APP) web page. The APP is housed in the National University of Singapore (NUS).