On October 6-7, leaders from Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkiye, and Uzbekistan will convene in Gabala, a mountain town in northern Azerbaijan, for the 12th summit of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). A three-hour drive from Baku, Gabala is a historic settlement now famed for its winter ski slopes.

“It’s one of the most beautiful places in the Caucasus,” Azerbaijani Ambassador to the United Kingdom Elin Suleymanov told The Diplomat. “It also has amongst the very best fruits in the country. And definitely the best pickles!”

The summit follows the September meeting of vice ministers in Bishkek and will see Azerbaijan take on the rotating presidency of the transnational organization. In addition to the five core members, Hungary, Turkmenistan, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (recognized only by Turkiye) will be present in Gabala as observer states.

Although the OTS headquarters is a modest red-brick building in Istanbul, the body now oversees a network of cultural initiatives, academic exchanges, and a common history textbook. Most recently, it has launched its own investment fund. But what role does the organization play among the shifting constellation of international groupings?

A Fraternal History

The intellectual roots of the OTS lie in pan-Turkism, an ideology that emerged in the 19th century and found wider resonance in the 20th. Political projects built on this idea have often faltered. Enver Pasha’s campaigns in Central Asia in the early 1920s ended in failure. Paradoxically, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founding president of Turkiye, who is often invoked by pan-Turkists, created a Turkish nationalism that was bounded by the borders of the new republic.

In 1992, Abulfaz Elchibey, Azerbaijan’s first democratically elected president, renamed the Azerbaijani language “Turkish” and made closer ties with Ankara a foreign policy priority. But his government collapsed within a year.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the idea of fraternal Turkic peoples gained new momentum. However, Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states were reluctant to simply fall under the influence of another “big brother.”

This has seen Turkiye change tack, framing engagement around equality, mutual respect, and recognition of each republic’s sovereignty. Turkish diplomatic cars in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Uzbekistan carry the number 01 on their red number plates, a sign that Turkiye was the first country to recognize their independence.

Ankara convened the first Turkic summit in 1992, although momentum slowed as Turkiye faced internal crises in the 1990s, while Russian influence reemerged. In the 21st century and under Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Central Asia has become more significant in Turkish foreign policy.

At the 2009 Nakhchivan summit, the current institution took shape. Then known as the Turkic Council, it was rebranded the Organization of Turkic States in 2021.

Language and Education

Today, the OTS focuses on practical steps toward cooperation. This includes a move taken in 2024 to institutionalize a 34-letter common alphabet based on the Latin script. Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan made the shift to a Latin script in the 1990s, while Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan’s moves in the same direction have been more labored. Kyrgyzstan, meanwhile, has seen no shift toward romanization.

Spoken language also remains a challenge. The OTS states span three different branches of the Turkic family: Turkish, Turkmen, and Azerbaijani in the Oghuz branch; Kyrgyz and Kazakh in the Kipchak branch; and Uzbek in the Karluk branch. Despite shared roots, the differences mean that Russian often remains the lingua franca in Central Asian and Azerbaijani diplomatic circles – something that irritates Ankara.

At the Bishkek summit, translation was pointedly made available in six languages (those of the core member states, plus English). I witnessed several journalists from the region’s Russian language media outlets vainly searching for the Russian option on their translation headsets.

Educational cooperation has been one notable area of success. Work began on a shared “Common Turkic History” textbook in 2014, an attempt to unify the region through shared collective memory. Suleymanov, the Azerbaijani ambassador to the U.K., also noted that Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan were the first to fund new schools in the “liberated territories” of Azerbaijan in 2023.

But the major impetus has stemmed from public and private initiatives from Turkiye, which have supported dozens of schools and universities across Central Asia since the early 1990s. This includes many schools and universities such as Suleyman Demirel University in Almaty and Atatürk-Alatoo University in Bishkek, which were established by the Gulen community. With the souring of ties between the Gulen movement and the Turkish government after the 2016 coup attempt, many of these private institutions became the center of a diplomatic battle as Ankara sought to establish control over them. In a victory for the Turkish government, they have since been absorbed into the state-run Maarif Foundation.

Kyrgyzstan’s Manas University, however, has always been a state-led scheme. Established jointly by Turkiye and Kyrgyzstan and funded by Ankara, it celebrated its 30th anniversary in September.

For Central Asian families, the appeal of a Turkish language education is obvious: high-quality instruction, the chance to learn Turkish, and the perception that the university is not corrupt.

“Even Kyrgyz officials comment on this,” said one Manas University professor, who asked to remain anonymous. “That is one of the first issues when they come to this university. They praise it for not being corrupt.”

This stands in marked contrast to Kyrgyz domestic institutions, where paying bribes to underpaid teachers has been a feature of the independence period.

Given the common linguistic roots, students adapt quickly to language learning, with Kyrgyz speakers taking a semester or less to make the transition.

Manas University in Bishkek celebrated its 30th anniversary in September. Photo by Joe Luc Barnes.

Economic Ties

The OTS took a large step toward institutionalizing its economic ties in 2024 when The Turkic Investment Fund (TIF) began operation.

According to its mission statement, the TIF is designed to foster “economic cooperation, increasing intra-regional trade and sustainable development across the Turkic world.” The fund’s capital, currently $600 million, is set to grow to around $3 billion over the next five years.

The fund presents itself as trying to complement other projects, rather than elbowing in on other institutional investors such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative or the EU’s Global Gateway. For many members, transport is the central concern, with the Trans-Caspian Middle Corridor becoming a shared focus. Running from Central Asia, across the Caspian to the South Caucasus and Turkiye, the corridor aims to triple its capacity by 2030.

Some concrete progress is already in evidence. The Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway opened in 2017 and was again modernized in 2024, while work continues on increasing capacity at ports on the Caspian.

Obstacles From Russia, China, and Other Alliances

While the numbers cited by the TIF sound impressive, they are small change in comparison to the 12 billion euros pledged by the European Union to Central Asia in April this year, while Chinese investment is several times larger still. Turkiye’s recent economic struggles add another layer of uncertainty, since Ankara is by far the largest economy in the OTS.

As a bloc, further integration of the OTS faces some obvious constraints. Each member is tied into other international arrangements: Turkiye belongs to NATO, and Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to the Eurasian Economic Union and the Russia-led CSTO.

These overlapping memberships complicate customs and trade. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are bound by EAEU tariffs, making it difficult to harmonize border procedures with Turkiye or Azerbaijan.

Anyone who has had to wait on a passenger train for three hours as it clears customs on the Uzbek-Kazakh border will be aware that official promises of a “simplified customs corridor” are still a way off.

Further, the Turkic world’s powerful regional neighbors are unlikely to treat steps toward Turkic unity without suspicion. Russia, China, and Iran all host large Turkic minorities. This includes Iran’s large Azeri population, Russia’s swathe of Turkic communities stretching from the Caucasus to Siberia, and minorities in China’s Xinjiang.

Central Asian governments have avoided any public criticism of China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other Turkic groups in Xinjiang, perhaps noting how much they rely on Chinese investment and consumer goods. In Turkiye, attacks on Chinese tourists in “retaliation” for the treatment of fellow Turkic peoples in the People’s Republic are also a thing of the past. Indeed, Devlet Bahceli, the leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (a longtime ally of Erdogan), even proposed a formal China-Russia-Turkiye alliance in mid-September, just prior to Erdogan’s visit to Washington.

In Moscow, while there is no public criticism of Kazakhstan’s closer defense cooperation with NATO-member Turkiye, public statements suggest that the Kremlin would be uneasy over increasing military ties between the two Turkic states. Even cultural initiatives can draw suspicion: Russian media worry about the potential loss of Cyrillic in Kazakhstan.

Iranian officials are alarmed at the plans for a “Zangezur Corridor” connecting a divided Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, Turkiye has recently discovered that there are limits to Turkic political solidarity: Central Asian states have pointedly declined to support Turkiye’s push for wider recognition of Northern Cyprus, preferring to avoid confrontation with Brussels.

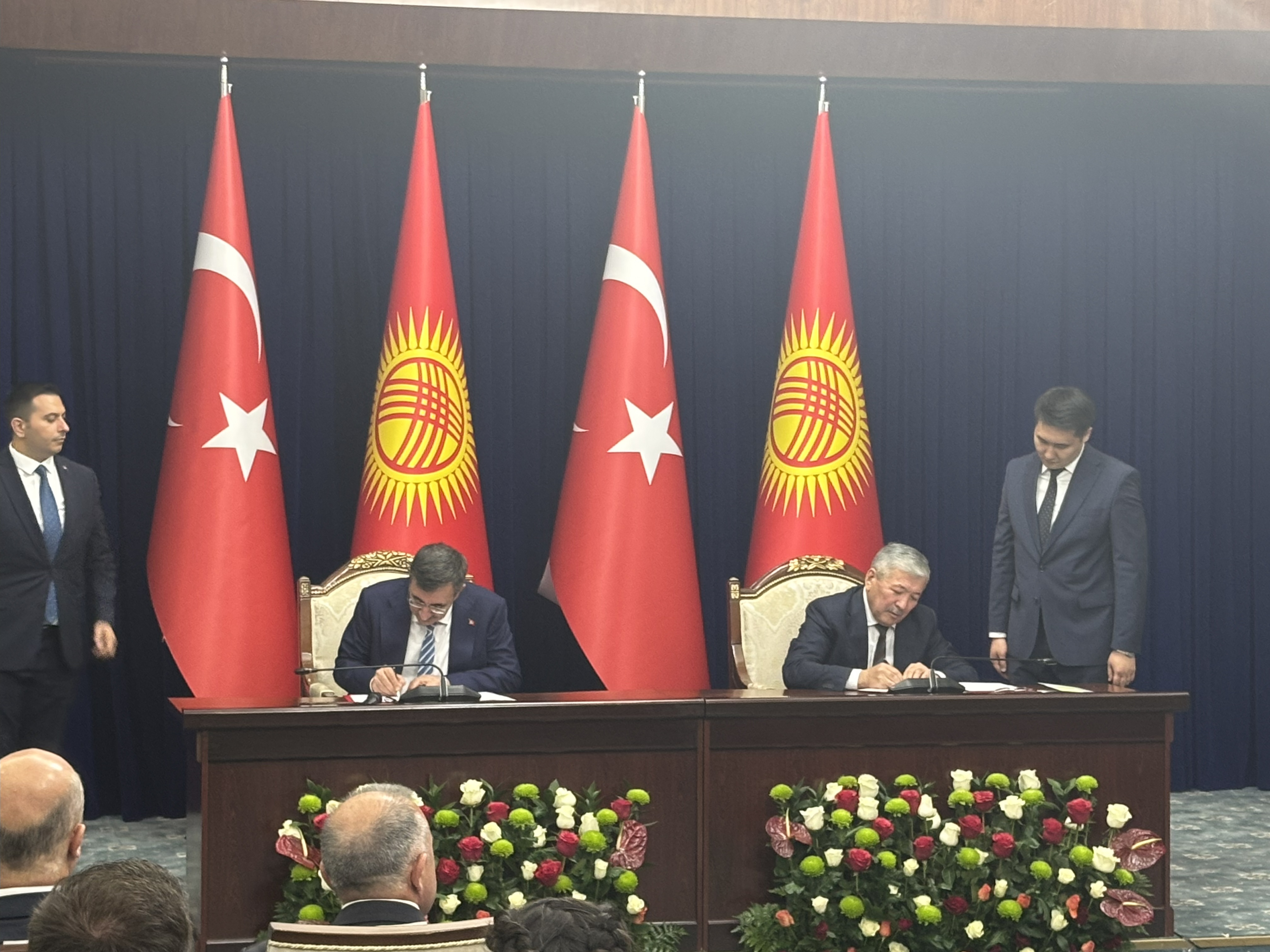

The Vice President of Turkiye, Cevdet Yılmaz, and the Chairman of Kyrgyzstan’s Cabinet of Ministers, Adylbek Kasymaliev, meet in Bishkek. Photo by Joe Luc Barnes.

The Road Ahead

For Suleymanov, this misses the point about what the OTS is seeking to achieve. “If you look at the world today, everything is boiling. You look to the north, there’s instability between Ukraine and Russia. You look to the south, there’s an ongoing tragedy in the Middle East. So I think the world should value the Organization of Turkic States. We want to promote education, cultural exchange, economic integration. And not only for us – this could benefit our neighbors. It already benefits Georgia and hopefully will benefit Armenia.”

One tailwind behind the OTS is that it seems to have secured the blessing of Western powers. There is strong U.S. interest in the Zangezur Corridor, particularly if it is eventually run under U.S. auspices. The Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, tentatively agreed to at an August 8 meeting in Washington between the prime minister of Armenia and the president of Azerbaijan, would aim to connect the Turkic world as goods transit across Armenian territory

“The final signing of the peace agreement, of course, would require the Armenian Constitution to remove any references to territorial claims against Azerbaijan,” said Suleymanov. This is an issue that may prove contentious, with analysts predicting that it may require an Armenian referendum to this effect.

Nevertheless, this is only part of a wider Western interest. “There is a consistent, strong interest from the U.S side,” said Suleymanov, who previously served as ambassador to the United States. “And we see similar interest from the U.K. too.”

Still, the OTS has already given the Turkic states a collective platform in an era when regional influence is often contested. “We have no other family. Our family is the Turkic world,” said Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev last year.

Families may argue, but they endure. The Gabala summit will not produce dramatic breakthroughs, but in a world of rising unpredictability, there’s nothing wrong with simply holding the course.