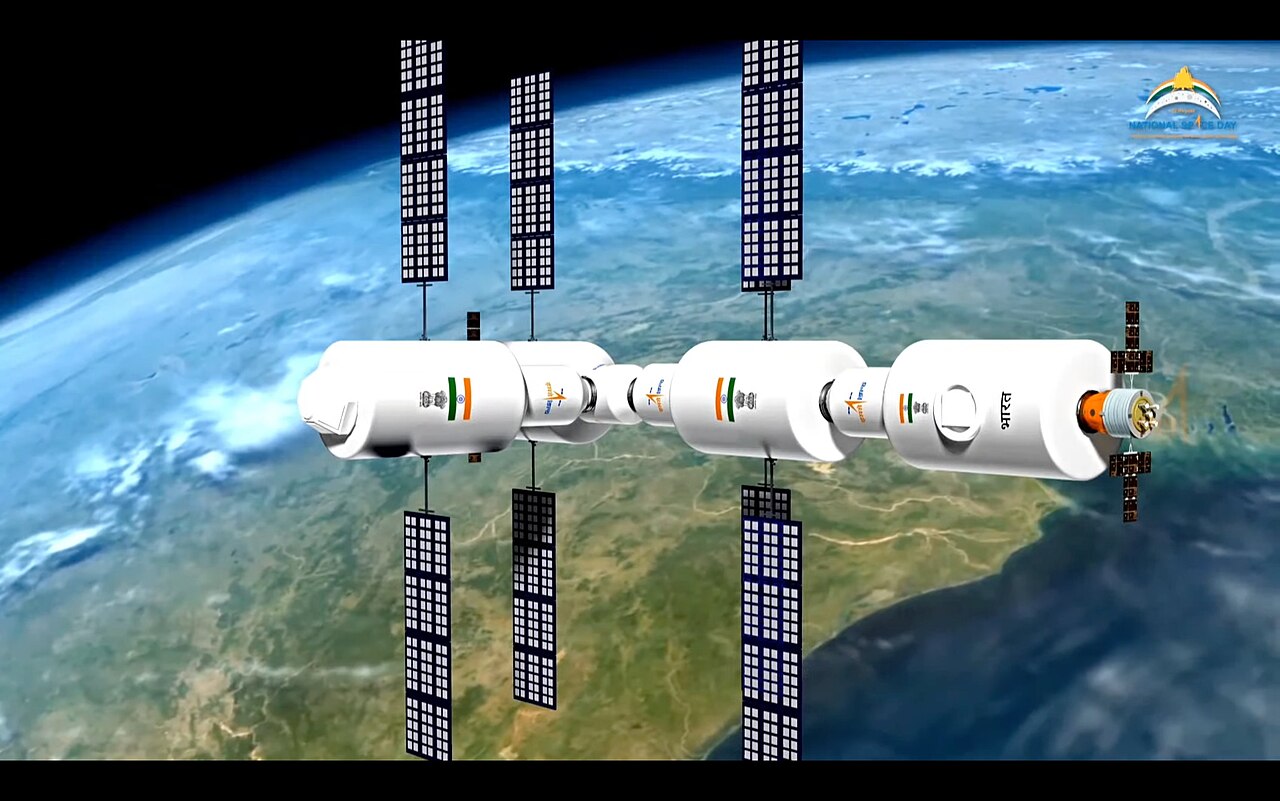

On August 23, National Space Day 2025, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would soon establish its own flagship national space station, unveiling a model of the previously-announced Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS), with the launch of the first module scheduled for 2028. Simultaneously, Modi also encouraged Indian startups to develop five space-tech unicorns within five years and increase the number of rocket launches to 50 annually, endorsing increased industrialization in the Indian space economy.

Meanwhile, in June 2023, India joined the Artemis Accords, a U.S.-led coalition focused on lunar exploration and cislunar governance. This decision grants India access to NASA partnerships, advanced space technologies, and an enhanced global presence. However, the unveiling of the BAS indicates that India aims to balance U.S. alignment with its own strategic autonomy, creating a paradox in India’s current space diplomacy efforts.

Is it possible for India to develop its own space station while participating in the Artemis Accords and leveraging advanced technology and market access? Can India maintain its neutrality amid the China-U.S. rivalry? How sustainable is this balance, given India’s constraints of finances, talent, and technology?

From Nonalignment to Pragmatic Hedging

India’s dual approach to space diplomacy is deeply rooted in its Cold War-era foreign policy. During this period, India adhered to a policy of nonalignment, refraining from siding directly with either the United States or the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, India sought to acquire crucial space technology from various sources, which significantly influenced its early space policy.

Under the guise of scientific cooperation, India collaborated with the USSR to launch its first satellite, Aryabhata, in 1975, and later for the Soyuz T-11 mission, which took astronaut Rakesh Sharma to the Salyut-7 space station. However, in the 1990s, following U.S. sanctions over alleged weapons proliferation, India began adopting self-reliant policies, developing indigenous technologies such as the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). Concurrently, liberalization allowed for selective engagement with the U.S. and European nations. Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) cooperation with NASA expanded in the 2000s; notably, the Chandrayaan-1 Mission in 2008 included U.S. technologies that aided in detecting lunar water.

This pragmatic hedging of India’s balancing act with multiple countries has continued into 21st century space diplomacy. Unlike the seemingly strict nonaligned stance of the past, India’s current approach seems to reflect a multialignment, as seen in the Artemis partnership, collaborations with Europe and Japan, and India distancing itself from the China-Russia International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) initiative.

The Artemis Accords and U.S. Partnership

In June 2023, India joined the Artemis Accords, marking a significant shift in its space diplomacy. Signed by over 40 countries, the accords establish rules for the transparency, interoperability, and responsible use of lunar resources.

India’s association with Artemis has several advantages. First, being part of this coalition grants India access to advanced space technology. For example, the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar provides India with high-resolution radar data applicable to agriculture and disaster management. Another instance is the Axiom-4 mission, which took an Indian astronaut, Shubhanshu Shukla, to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2025 – a significant development considering ISRO’s upcoming Gaganyaan mission. These examples show how such an association can offer India capacity-building opportunities that might otherwise be unavailable.

Second, by joining Artemis, India elevates itself from a peripheral space economy and gains international visibility. This visibility aligns with India’s aspirations to achieve a leadership position in the Global South and become a major global player in space governance.

Third, this association indicates the direction in which India is leaning. It joins countries such as Japan, France, and Australia, seemingly in opposition to the China-led ILRS initiative.

However, the Artemis framework and India’s involvement present several challenges, particularly concerning the accords’ plans for future lunar resource extraction. Many have criticized these plans as being skewed in favor of U.S. commercial interests. For decades, India has championed equitable access to outer space and its peaceful use. This stance might eventually clash with the Artemis Accords, especially as India represents the Global South in international forums such as the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) Furthermore, if the China-U.S. rivalry intensifies in the coming years, India might be compelled to take a more definitive stance and align with Washington’s objectives, which would contradict India’s historically flexible space diplomacy.

The Push for Strategic Autonomy: Enter the BAS

An artist’s depiction of the Bharatiya Antariksha Station, which was unveiled on India’s National Space Day 2024. Image via ISRO.

While signing the Artemis Accords aligns India with a U.S.-led coalition, the introduction of the BAS underscores New Delhi’s ongoing pursuit of autonomy in its space policy. During the National Space Day event at Bharat Mandapam, Modi announced that “the day is not far” when India will have its own space station. He unveiled a scale model of the BAS, envisioned as a modular platform to be operational by the early 2030s.

The BAS announcement is significant for several reasons. First, it grants India greater sovereignty over its human spaceflight infrastructure. For years, India has depended on foreign collaboration, but the BAS would eliminate this reliance, allowing Indian astronauts more autonomy in space.

Second, much like how the PSLV became synonymous with India’s independent launch capabilities, the announcement of the BAS has enhanced India’s national pride and technological prestige. This development would position India among an exclusive group of countries (including China and the United States) with a permanent human presence in space.

Third, the BAS provides India with strategic insurance in an increasingly fragmented global space economy. With the U.S. focused on the Artemis framework and China on Tiangong (its own space station) and the ILRS with Russia, the BAS system ensures that India does not have to rely entirely on foreign space architecture for its space missions.

However, India faces several challenges in this regard. The operational costs of a space station are estimated at approximately $3 billion a year, as shown by NASA’s funding for the ISS, while ISRO’s annual budget is a modest $1.7 billion or so. Another challenge is the development of necessary equipment for astronauts, including life-support systems, EVA suits, and long-duration astronaut training. Heavy investment in the BAS also risks diverting funds from commercial ventures such as Earth observation or climate technologies, which can yield more immediate returns.

India as a Global South Voice

Alongside joining the Artemis Accords and unveiling the BAS, India has been pursuing a strategy of multilateral hedging. This approach prevents India from being locked into any single bloc while allowing it to maintain its legitimacy as a representative of the Global South.

At UNCOPUOS meetings, India has consistently maintained that space is the “province of all mankind,” upholding the principles enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty of 1966. This principle emphasizes equitable access, sustainability, and capacity building for emerging space actors. This is particularly crucial for nations in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, which often face the risk of exclusion from space governance discussions that are dominated by major space powers.

India has earned the reputation of a “frugal innovator” with its Mars Orbiter Mission (2013) and Chandrayaan-3 mission (2023), which were developed at a fraction of the cost of Western space missions. Furthermore, India provides developing nations with satellite data and capacity-building programs, offering non-space nations the opportunity to participate in the global space economy.

This stance contrasts with the China-led ILRS program, which serves as an alternative to the Artemis Accords. While China claims that the ILRS is an open initiative, it is largely seen as China-centric. In contrast, India continues to advocate for inclusivity and consensus, positioning itself as a “bridge actor.” This means that while India aligns with Artemis for technology, it also demonstrates independence with the BAS and emphasizes legitimacy at UNCOPUOS.

What Are the Structural Constraints of India’s Balancing Strategy?

Efforts to balance Artemis alignment, the BAS initiative, and Global South leadership present significant structural challenges for New Delhi, raising questions about the sustainability of this strategy.

Funding is one of the most significant challenges in this regard. As a capital-intensive industry, the Indian space economy has long payback periods. This is despite the Indian government’s introduction of measures such as the 5-billion-rupee Technology Adoption Fund and the removal of several restrictions on foreign direct investment. However, private capital investment remains limited. In fact, funding in the space sector fell by 55 percent in 2024, dropping from $130.2 million to $59.1 million. To sustain initiatives like the BAS, stronger procurement commitments are needed from ISRO, the armed forces, and civilian agencies.

Access to technology is another challenge. Although India has joined the Artemis framework, access to key subsystems such as advanced avionics, propulsion, and deep-space communication remains limited owing to U.S. restrictions on export control regimes such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. Therefore, India must develop indigenous alternatives or negotiate carve-outs to reduce its reliance on foreign suppliers, which may affect its autonomy.

There is also a lack of sufficient educational and training programs. Although India produces thousands of engineers annually, only a few specialize in cryogenics, life-support systems, or orbital robotics. These specializations are essential for a program like the BAS to succeed.

Finally, escalating geopolitical tensions between the United States and China over lunar resources and cislunar security might compel India to side with the U.S. and compromise its hedging strategy. However, remaining too independent might isolate India from Artemis-linked supply chains and funding streams.

Scenarios for India’s Space Diplomacy, 2025-2035

Over the next decade, India’s balancing act between the Artemis partnership and strategic autonomy could unfold in three different ways.

In the first scenario, India heavily relies on the Artemis Accords, with U.S.-led frameworks forming the backbone of its lunar activity. NASA offers training to Indian astronauts, scientific collaboration intensifies, and ISRO’s spaceflight missions become integral to the Artemis Gateway projects. Meanwhile, the BAS initiative is more symbolic, facing budget cuts or delays, as India sacrifices some autonomy to become a trusted junior partner in the U.S.-led Artemis order.

In the second scenario, the BAS becomes the cornerstone of India’s space strategy. Despite funding challenges, continued political support and industrial partnerships propel the BAS to operational status by the 2030s. India emerges as a leader in the Global South, with the BAS serving as an alternative to the U.S.-led Artemis and China-led ILRS. However, while this scenario enhances India’s strategic autonomy, it may isolate the country from accessing advanced technologies.

In the third scenario, India strikes a balance by aligning with Artemis for access to technology, markets, and prestige, pursuing the BAS initiative for sovereignty and symbolism, and maintaining legitimacy at UNCOPUOS meetings. Although the BAS may face delays, its ongoing development allows India to preserve its independence. Additionally, India becomes a bridge power, balancing its relationship with the United States while maintaining credibility within the Global South. This scenario demands sustained investment and expert diplomacy, heavily relying on a policy of multialignment.

The Future of India’s Balanced Space Strategy

By joining the Artemis Accords and launching its own space station initiative, India demonstrated both an intent to side with the U.S. and an emphasis on sovereignty through the BAS, while also showcasing inclusivity at UNCOPUOS.

The announcements made on National Space Day 2025 solidified the push for a balanced space policy. The BAS initiative, especially, underscored a continued commitment to sovereignty and an autonomous presence in orbit while maintaining international collaborations.

However, the success of this multifold strategy will depend on how India manages its structural constraints, such as funding, access to technology, and talent development, among others. If India succeeds in this balancing act, it could emerge as a rule-shaper, rather than just a participant, in the global space economy.

Ultimately, India’s space future will not be determined just by whether it sides with the U.S.-led Artemis program or chooses its own autonomy. It will depend on whether India can balance independence and alignment without being cornered into choosing a side amid the 21st century’s ever-changing geopolitics.