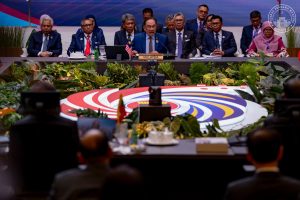

The 47th ASEAN Summit is scheduled to take place later in Kuala Lumpur later this month. Among the items likely to shape the summit discussions is Indonesia’s proposal – announced at the July 2025 ASEAN Ministerial Meeting – to expand ASEAN membership to Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea.

Timor-Leste’s accession, which has been formally under discussion by ASEAN over the last several years, is expected to be finalized at this month’s summit. But rather than strengthening ASEAN, this move to expand could instead weaken, and potentially fracture, the bloc.

The proposal comes at a time when ASEAN faces mounting pressure to prove its relevance amid deepening internal divisions and intensifying geopolitical competition in the Indo-Pacific. Jakarta’s push reflects an ambition to assert Indonesia’s leadership within ASEAN and position the bloc as more cohesive, regionally effective, and relevant. And yet, will a bigger ASEAN be a stronger ASEAN? Or will further enlargement, particularly without a parallel focus on internal reform, further undermine the very cohesion the bloc seeks to build?

Admitting Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea into ASEAN risks weakening cohesion at a time when the bloc is already struggling to overcome deep economic, political, and security divides. It also raises deeper questions about ASEAN’s strategic identity and its role in Indo-Pacific security.

ASEAN has expanded before. The bloc’s last enlargement in the 1990s, which brought in Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia, reshaped ASEAN’s geopolitical footprint and laid the groundwork for today’s fast-growing market of 680 million. Timor-Leste, largely due to Indonesia’s advocacy, has been on the path to membership since 2022, despite considerable skepticism among other ASEAN members. Papua New Guinea, by contrast, has only recently entered the conversation and has far weaker historical, political, institutional, and economic ties to Southeast Asia.

Enlargement should serve ASEAN’s core goals: consensus-based governance, economic integration, strategic autonomy, regional solidarity, and a unified regional identity. A central question is whether ASEAN is prepared – and able – to bring Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea into alignment with these ambitions, particularly at a time when the bloc is already having difficulties meeting them and economic integration has stalled. Adding two fragile states without parallel internal reforms within the bloc could make consensus harder, widen economic divides, and obscure the bloc’s strategic identity.

Governing by Consensus: Challenges to Bloc Cohesion

Consensus is at the heart of ASEAN decision-making, a model that already struggles to deliver, given the 10 member states’ widely divergent political systems, developmental levels, and geopolitical alignments. The bloc’s struggle to respond decisively on the crisis in Myanmar, resolve maritime disputes in the South China Sea, or develop a coherent strategy on great power competition reveals the limits of the consensus approach.

Consensus only works when members can align on shared priorities and have the state capacity to negotiate and act on collective commitments. Neither Timor-Leste nor Papua New Guinea meets that standard. Both frequently diverge from ASEAN norms in international forums.

Timor-Leste’s political, security, and economic fragility undermines its independence in ASEAN matters. Furthermore, Timor-Leste’s vulnerability has led to a significant orientation toward China, illustrated by Beijing’s financing of the Presidential Palace, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Armed Forces Headquarters, and reinforced in 2024 by the two nations’ joint announcement on “strengthening of the comprehensive strategic partnership.” Papua New Guinea’s U.N. voting alignment is closer to Australia and New Zealand than ASEAN members, reflecting its stronger ties to Pacific blocs, most recently underscored in the announcement of its mutual defense alliance with Australia.

These divergent priorities in both countries are compounded by weak governance and limited state capacity. In Timor-Leste, underdeveloped state institutions and near-total economic reliance on dwindling petroleum revenues leave the government vulnerable to volatility and a populace heavily dependent on the public sector. A 2025 World Bank report estimated that public expenditures in Timor-Leste averaged 85 percent of GDP between 2013 and 2023, with 42 percent of citizens living below the national poverty line and 88 percent of formal employment in the public sector. Meanwhile, low labor force participation, anemic economic growth, and a lack of infrastructure investment persist despite decades of foreign aid. The depletion of Timor-Leste’s Petroleum Fund further darkens the country’s future viability.

Papua New Guinea faces even steeper hurdles: a fragmented territory, weak rule of law, political instability, and high vulnerability to shocks. A vast majority – 86 percent – of its population lives in rural areas, many without road access and limited access to public services. The government has struggled to maintain public order, with political unrest escalating into deadly riots in the capital Port Moresby in 2024, and the Asian Development Bank classifying Papua New Guinea as a fragile and conflict-affected state.

ASEAN already struggles to reach consensus on high-stakes issues including the South China Sea, Myanmar, and regional environmental challenges such as those in the Lower Mekong Subregion. Adding two new members with divergent alignments, weak institutions, and limited policymaking bandwidth risks slowing an already fractured decision-making process and undermining the bloc’s efforts for unified action.

Regional Economic Integration: Widening the Development Gap

In addition to striving for effective consensus, regional economic integration has long been central to ASEAN’s vision. This goal of building a single market and production base was formalized in 2015 with the launch of the ASEAN Economic Community. Despite some success in initiatives such as the ASEAN Single Window, the broader goal of a cohesive economic community has been hindered by wide and persistent economic development gaps among the ten member states. The Initiative for ASEAN Integration, launched to address these gaps, has delivered limited results.

Admitting Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea would widen economic disparities among ASEAN members and make economic convergence within the grouping even more difficult. Both countries rank among the least developed economies in the Asia-Pacific. Their human capital index scores – 0.45 for Timor-Leste and 0.43 for Papua New Guinea – fall short of the regional average of 0.59. Multidimensional poverty affects 48 percent of Timor-Leste’s population and nearly 57 percent of Papua New Guinea’s population, much higher than other rates in the region. Stunting rates in both countries are close to 50 percent, almost double the ASEAN average of 27 percent.

Timor-Leste’s economy is heavily dependent on petroleum exports, with withdrawals from the Petroleum Fund accounting for 88 percent of GDP. The fund is expected to be depleted by the mid-2030s when the country will face the long-predicted “fiscal cliff” unless new fields emerge. In Papua New Guinea, resource exports from extractive industries including oil, natural gas, and gold drive GDP growth, but deliver little improvement in public services or infrastructure; little more than 20 percent of the population has electricity.

Furthermore, neither of these economies are clearly oriented toward ASEAN. While Papua New Guinea exports to Singapore and Malaysia, its other primary export destinations include Australia, China, and Japan. As a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, Papua New Guinea is oriented toward Pacific institutions rather than ASEAN, and its participation in regional trade agreements rooted in the Pacific contrasts with the country’s lack of meaningful trade link to Southeast Asia. Timor-Leste’s trade is somewhat more ASEAN-facing, but in 2023 its imports ($904 million) vastly exceeded its exports ($294 million), leaving its overall trade volume low and making it a marginal economic partner within ASEAN.

ASEAN’s economic integration already suffers from credibility concerns. Admitting two disconnected and fragile economies would widen existing development gaps and make ASEAN’s goal of a single market and production base even more elusive.

Strategic Identity: What (and Who) is ASEAN?

Beyond questions of ASEAN’s governance and economic integration, ASEAN’s proposed expansion forces the bloc to confront the more existential question of its identity: is it a geographically bounded association, an economic bloc, or a strategic community? This is not just an immediate ASEAN concern. For the United States, Japan, India, South Korea, Australia and others, ASEAN’s ability to define its identity, its membership standards, and maintain coherence as a counterpoint to Chinas is crucial to their Indo-Pacific strategies.

While there may be a geographical argument in favor of expanding ASEAN membership to Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea, geography alone should not define ASEAN membership. It is true that Timor-Leste shares the island of Timor with Indonesia’s West Timor and Papua New Guinea borders Indonesia’s easternmost provinces of Papua and West Papua. If proximity justified membership, however, the same logic could extend to the Solomon Islands, Bangladesh, or even Australia. Such inclusions would distort ASEAN’s foundational identity as an association of Southeast Asian nations under the mantra of “One Vision, One Identity, One Community” that it already struggles to realize.

More pressing than geography is the question of strategic orientation. Papua New Guinea has historically oriented itself toward Melanesia, Oceania, and the Pacific, rather than aligning with Southeast Asia. It is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum and participates in a range of Pacific economic initiatives, including the South Pacific Regional Trade, Economic and Commercial Agreement and the non-reciprocal Agreement on Trade and Commercial Relations between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Timor-Leste has closer ties to ASEAN but remains a marginal actor with limited engagement as an ASEAN observer. It has yet to demonstrate a strategic convergence with the bloc’s long-term priorities.

Admitting members without clear alignment risks diluting ASEAN’s strategic purpose. Any enlargement must be driven by strategic and economic criteria that advance the bloc’s core goals, vital interests, vision for the regional security architecture, and foundational principles enshrined in its Charter and the Political-Security, Economic, and Socio-Cultural 2016-2025 Blueprints. That case has yet to be made for either candidate.

ASEAN now faces a challenging trade-off between cohesion and expansion. At this moment, the bloc must prioritize cohesion to demonstrate credibility and relevance. Expansion can come, but it should be criteria-based and require comprehensive reforms to members’ governance, economies, and strategic orientations to ensure that ASEAN remains not just inclusive but effective. Without achieving greater unity, economic clout, and a common strategic vision first, adding members will deepen divisions and weaken an ASEAN already widely perceived as increasingly fragmented and indecisive.