Peach oolong, pink guava, and passionfruit: these are flavors you’d expect to find in a bubble tea shop, not in a black market vape loaded with illicit drugs. So it’s no surprise that young people in Southeast Asia have taken to these seemingly harmless devices. Some call them “piao piao”; others, “k-pods” – but perhaps their most fitting moniker is “zombie vapes,” since puffing the fruity concoctions has been known to leave users twitching uncontrollably, staggering around with glassy eyes, or convulsing on the floor.

A surge of recent incidents has turned this issue into a fast-growing public health concern. Yet, like the undead they’re named after, these zombie vapes aren’t so easy to wipe out.

Vapes, also known as e-cigarettes, are a lucrative $30 billion industry with around 82 million users worldwide. Even in Southeast Asia – where they are banned in Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam – there’s a thriving $920 million market, according to consulting firm IMARC Group. But while they were once intended as an alternative to traditional cigarettes, newer versions no longer deliver merely nicotine. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), vapes have rapidly evolved to contain new psychoactive substances, which mimic the effects of controlled drugs but are cheaper and easier to obtain – all while bypassing legislation.

Mixed into the zombie variations is one such substance: etomidate. As a medical anesthetic, etomidate is typically used to sedate patients for short operations. But in its new life as a street drug, it’s being inhaled through e-cigarettes, supposedly to imitate the high of ketamine. Etomidate has been an issue in East Asia for a while, with South Korea having designated it as a drug of concern in 2020 and China identifying it in e-liquids since 2021. Over the past year, however, etomidate has started to appear in illicit markets across Southeast Asia.

From Singapore and Thailand to Cambodia, Indonesia and Malaysia, illicit etomidate has been found in drug samples all around the region.

“Its emergence fits into the wider pattern of a diversifying synthetic drug trade,” explains Benedikt Hoffman, UNODC representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. “Methamphetamine remains the dominant drug, but organized crime groups have actively looked for alternatives, especially as enforcement pressure on meth routes grows.”

To that end, e-cigarettes have been a useful vehicle for delivery since they are ubiquitous in Southeast Asia. Despite vape regulations being over 30 percent more prevalent in the region compared to the rest of the world, vaping is widespread, particularly among young people. In Cambodia, for instance, 82 percent of vape users are 15 to 35 years old. In Singapore, over half of those caught vaping are under the age of 30. The presence of this active, albeit illegal, vaping culture has made it easy for etomidate-laced vapes to slip under the radar, especially since they are outwardly indistinguishable from their nicotine-only counterparts.

“Drug trafficking syndicates in the region have always been quick to capitalize on trends and adjust distribution channels,” says Hoffman. “Selling etomidate in e-cigarettes takes advantage of the current boom of these devices across East and Southeast Asia.”

The spread of these zombie vapes largely takes place on online platforms, where they have been openly and liberally sold to children as young as 13. As a white paper from the National University of Singapore’s school of public health found, e-cigarettes in Southeast Asia are widely available on e-commerce websites like Lazada, social media platforms like TikTok, as well as encrypted messaging apps like Telegram. Age verification is seldom, if ever, conducted. In fact, sellers hone in on young customers by appealing to them with influencers, local celebrities, sweet flavors, and candy-colored designs. Some dealers have even taken to peddling zombie vapes near schools or getting adolescents to sell them to their peers – often falsely assuring naive buyers that etomidate doesn’t show up in urine detection tests.

The cheery marketing and peer-to-peer promotion tends to mislead people into underestimating the severity of the drug.

“Most young users do not appear fully aware of the kind of substance they are consuming,” says Leslie Goh from We Care Community Services, an addiction treatment center in Singapore. “They tend to view k-pods as an offshoot of nicotine vapes.”

But etomidate, when abused and inhaled in vaporized form, can pose serious dangers. Studies have found that the use of etomidate-laced e-cigarettes can lead to severe hypokalemia, muscle weakness and breathing difficulties. Chronic overdoses of the substance can result in irreversible brain damage and various mental disorders. Yet, its addictive properties keep users coming back for more. Etomidate’s rapid onset, short duration of action and low cardiovascular risks – the very traits that make it effective as a medical anesthetic – quickly bring about physical and psychological reliance.

“In addictions, the faster you can give a person a high and the fewer the after-effects, the more likely they are to get dependent on the drug,” says Dr. Munidasa Winslow, a senior psychiatrist at Promises Healthcare. “That’s what has happened with etomidate.”

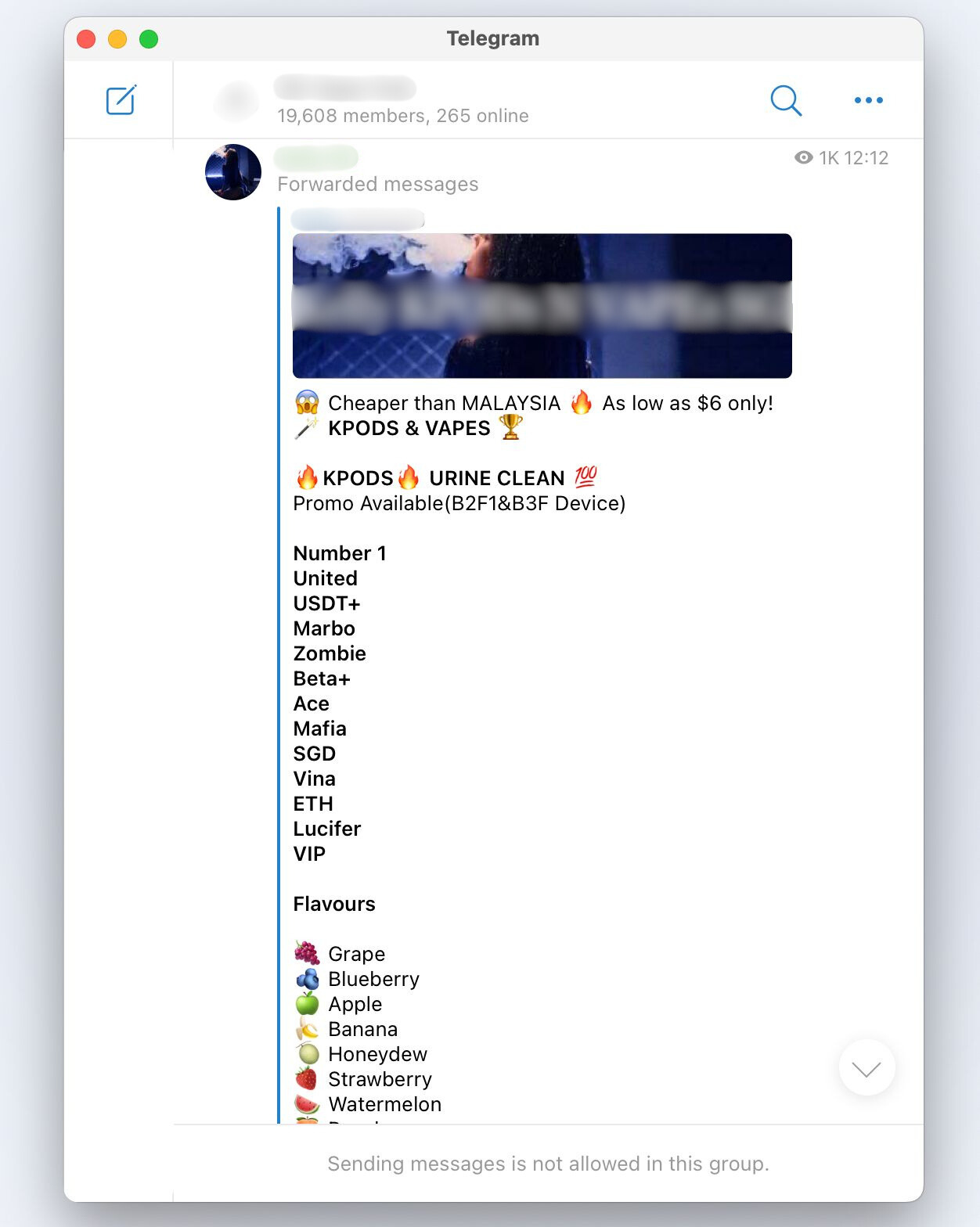

A screenshot of a Singapore-based Telegram group advertising etomidate-laced vapes (“K-pods”). (Nicole Fan)

One user shared that he would even puff his drug-laced device at the steering wheel.

“At the time I did not feel like it was affecting me at all, but my colleagues had videos of me driving erratically,” they said.

While that user is now in treatment, etomidate’s disorienting effects have already led to several fatalities. In Singapore, where around one in three vapes contain etomidate, multiple teenagers have passed away after falling off buildings during their etomidate highs. The substance was also detected in the blood samples of two people killed in a car accident, who were found to have dozens of vapes in their vehicle.

The safety risks can be exacerbated by processes in the supply chain. As the UNODC has highlighted, the etomidate within these e-cigarettes isn’t necessarily diverted from legal, clinical sources; it is also manufactured from scratch in illegal and dubious ways. During a recent raid in Bangkok, for example, Thai authorities discovered a warehouse with over 2,000 liters of chemicals, which were intended to produce 200 kilograms of etomidate and fill 600,000 vapes. Such bootleg methods are meant to reduce operational costs and evade potential detection – but they’re often practiced with little technical or scientific knowledge, as the International Narcotics Control Board has reported. Production can take place in non-sterilized settings and the same equipment can be used for different outputs, paving the way for unintentional contamination and unpredictable chemical mixtures.

Most East Asian countries – including China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan – have already listed etomidate as a controlled substance. But the crackdown in Southeast Asia is only just beginning. Singapore is most notable in its “whole-of-government” approach, which it announced in late August this year. This includes legislating etomidate as a controlled drug, raising the penalties for vapers, stepping up public surveillance and launching educational campaigns. Digital platforms are under close scrutiny too: over 600 vape channels on Telegram and more than 6,000 e-cigarette online listings have been removed by the country’s authorities. Elsewhere in the region, Cambodia listed the manufacturing of vapes as a negative investment in June, Thailand reclassified etomidate as a controlled substance in July, and Malaysia announced that it would be moving towards a nationwide ban on vapes in September.

Vape lobbyists have been quick to denounce the policies. Malaysia’s plan was deemed “unfairly punishing” by the country’s e-cigarette association, while Singapore’s strategy was criticized by CAPHRA, a New Zealand-based pro-vaping alliance, for “fear-mongering.” The alliance argued that a blanket ban on vapes, including nicotine-based ones, would deprive smokers of an important harm reduction tool. But authorities are standing firm.

“The vapes themselves are just a delivery device,” Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong noted in a speech in August. “Right now, it is etomidate. In future, it could be something worse – stronger or far more dangerous drugs.”

That future has arrived sooner than expected. Based on Winslow’s experience, vape users are already experimenting with drugs beyond etomidate.

“Some of my patients know how to lace their vapes with almost everything, from liquid meth to liquid cannabis,” he says.

Dealers are also devising new tactics to minimize their exposure to law enforcement, including setting up shell companies and outsourcing storage to local actors. Meanwhile, vape shops that have managed to evade detection are still selling their products on online platforms, sometimes disguised as “nasal inhalers” or “inhaled essential oil.”

One Telegram channel that has remained in operation in Singapore has close to 20,000 members. Far from backing down after the new laws were introduced, it continues to market e-cigarettes, including those of the “zombie” variety, every day. But alongside vapes, it also advertises prostitution services and online jackpots. Such cross-promotion is indicative of the growing convergence between drug trafficking syndicates and other criminal groups, the UNODC noted in a report on synthetic drugs in the region. It also opens a gateway for the primarily young vape buyers to wade further into other criminal offenses.

Social workers highlight the need to tackle the issue’s deeper roots. Gopal Mahey, a senior counselor at the Centre for Psychotherapy, observes that clients dependent on drug-laced vapes usually share common traits such as unresolved trauma, emotional distress, and intergenerational patterns of substance use.

“For young people, k-pods not only deliver substances like etomidate, but also emotional relief, escape, and comfort,” he says. “As long as self-soothing through substances feels like the easiest option, new forms of drug-laced vapes will continue to surface.”

Treatments like individual therapy, support groups and psychoeducation can address these underlying issues and help people with long-term recovery. But Dr. Rayner Tan, a social and behavioral researcher at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore, points out that many factors impede access to these interventions – including cost, stigma, and the fear of legal consequences.

“These factors widen the equity gap for groups who are already socioeconomically disadvantaged, or vulnerable and marginalized,” he explains.

It’s a timely warning given that the number of people using illicit drugs worldwide has reached a record high, according to the UNODC, with levels of drug use amongst young people surpassing that of past generations. Zombie vapes are but one piece of a sprawling puzzle, with important social and psychological dimensions that have yet to be fully understood.

As Tan puts it, “we definitely need to recognize that this may be just a symptom of a much more hidden epidemic among our youth.”