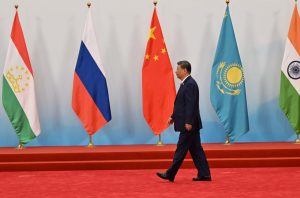

The global spotlight is on China this week: first on the port city of Tianjin where the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) held its annual leaders’ summit on September 1 and soon on Beijing, where China will commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Pacific, or as it’s known in China, the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

In promoting these two events, China has highlighted the sheer number of world leaders flocking to the country. The SCO reportedly had more than 20 foreign leaders and the heads of 10 international organizations in attendance. Beijing expects 26 foreign leaders to attend the September 3 parade.

In focusing on these numbers, as many media reports do, one can draw the conclusion that the SCO must matter.

But it’s not the SCO that matters, it’s China. And China is why Central Asia still cares about the SCO, even as the SCO has evolved away from its focus on the region.

The organization was dedicated to Central Asia in the beginning. It was founded as the Shanghai Five in 1996, encompassing China, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan, before the SCO was established in 2001 with the inclusion of Uzbekistan. For the Central Asian states, the SCO remains a key forum, even if very little about the SCO is directly about Central Asia anymore.

It’s no secret that China and Russia have driven the SCO’s expansion — each for their own reasons — and with its expansion the organization’s focus has become diluted. The additions of India and Pakistan (2017), Iran (2023), and Belarus (2024), have grown the SCO’s heft, but not necessarily its effectiveness.

Eva Seiwert, in The Diplomat Magazine last year, wrote: “The SCO’s shifting focus aligns most obviously with China and Russia’s evolving interests in the organization.” Seiwert went on to note that in including India and Pakistan, the SCO bet on “increasing its visibility on the world stage, while accepting the risk that decades of India-Pakistan tensions could weaken its core security cooperation mandate.” Iran, she argued, made a more natural inclusion on the back of shared interests but further fractured its regional focus and damaged whatever legitimacy had been gained by including democratic India. Belarus’ inclusion sealed “the SCO’s transformation from a focused group of Central Asian states intent on improving the regional security situation into a geopolitical bloc at the center of a hardening global confrontation between the U.S. and its allies on one hand and China, Russia, and the partners they are collecting on the other.”

Even when Central Asia was the core of the SCO, then, regional states were not calling the shots. Russia and China were. In the aftermath of the Astana SCO summit last summer, Alexander Piechowski argued in The Diplomat that Russia was “increasingly a junior partner” and that the 2024 summit highlighted “China’s gradual overtaking of Russia in the SCO region.”

If anything, Tianjin — and the international response to the summit — drives that point home.

The Tianjin Declaration begins with now standard Chinese rhetoric about “profound historic changes” in the international sphere, and the supposed evolution of the international system toward a “more just, equitable, and representative multipolar world.” There is a barely-veiled swipe at the United States — “The global economy, particularly international trade and financial markets, has suffered severe shocks” — and predictable language about the United Nations’ importance but the need for reform. The declaration naturally cites the “Shanghai Spirit” of “mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for diverse civilizations, and pursuit of common development.”

Rather perversely — given that Russia is actively engaged in a war of territorial expansion in Ukraine — the declaration states that its members “advocate respecting the right of people of all countries to independently choose their own path of political, economic and social development, and emphasize that the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity, equality and mutual benefit, non-interference in internal affairs and non-use or threat of use of force are the basis for the stable development of international relations.”

The members, in the declaration, also apparently reiterate “their opposition to resolving international and regional hot-spot issues through grouping and confrontational thinking.”

Nothing says opposition to “grouping” like a summit and a group declaration.

Despite the fact that the statement also reiterates “that Central Asia is the core area of the SCO” and that it has “supported the efforts of Central Asian countries to maintain peace, security and stability in their own countries and the region,” there is little about Central Asia specifically in the content and context of the contemporary SCO.

In the Tianjin Declaration, Kyrgyzstan merits mention given that it is next in the rotating roster to hold the SCO’s presidency and host the annual summit. Uzbekistan is mentioned in context of hosting the SCO+ security dialogue. Kazakhstan gets a mention related to its plans to host a U.N. regional climate summit in 2026. The Tianjin Declaration even mentions that construction on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway has started.

Central Asia’s interests are woven throughout the statement, in language regarding counterterrorism and drug trafficking, but very little about the SCO is Central Asia-specific.

And frankly speaking, the Central Asian states aren’t all that bothered. Why? Because while the SCO has evolved and its mission expanded (or been diluted, depending on your perspective), Central Asia’s interests in the SCO have also evolved. Although Central Asian leaders remain interested in the SCO’s security aspects — for example the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS) — what regional capitals really want is a respected place at the table. And at the SCO, they get that.

All five Central Asian presidents are in Beijing. All five scored bilateral meetings with Xi Jinping and other top Chinese leaders; most had bilateral meetings with Russian President Vladimir Putin, too, as well as other world leaders in attendance. All of the Central Asian presidents have had busy schedules this week. For example, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev met with the leaders of Huawei, China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), and others; Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev had his own meeting with dozens of Chinese business leaders.

To a certain extent, for the Central Asian states, the SCO has become a venue for deepening relations with China and managing relations with Russia. It also links Central Asia to a wider community of states beyond the China-Russia duo, and provides a forum for Central Asian states to voice their perspectives sans judgement regarding their autocratic tendencies.