The South Korea-U.S. alliance has entered a decisive phase. Long defined by the North Korean threat, the partnership has, over the years, steadily expanded into new areas, ranging from defense industry cooperation to advanced technologies. Yet, at its core, it remains haunted by legacy disputes: the role and scope of U.S. Forces in Korea (USFK), Washington’s demand for greater strategic flexibility, and the unresolved question of wartime operational control transfer. Against this backdrop, the search for new domains of collaboration that can transcend peninsular debates and anchor the alliance in global issues has never been more urgent.

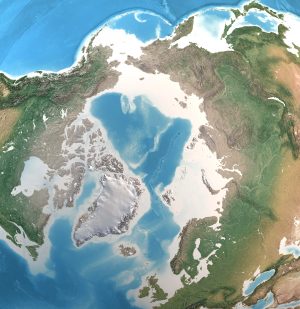

One such domain could be the Arctic, particularly the North Pacific Arctic. Long considered distant from Northeast Asia’s flashpoints, the Arctic is now emerging as a site where great-power rivalry, maritime innovation, and climate change intersect. For Washington, Alaska is a strategic hinge linking homeland defense to the Indo-Pacific. For Seoul, the Arctic is both an economic opportunity and a stage on which to assert itself as a green maritime power and legitimate non-Arctic stakeholder. If harnessed strategically and systematically, these converging interests could transform the alliance from a security arrangement tethered to old, albeit still very much alive, inter-Korea disputes into a multidimensional partnership that engages the most pressing challenges of the 21st century.

South Korea’s Arctic Interests

South Korea has been quietly building a serious Arctic profile. With its eyes on the rapidly opening sea lanes, Seoul recently announced that it would begin pilot operations through Arctic shipping routes in 2026, and thus a government task force has been set up to oversee trials and draft a long-term Arctic roadmap. As part of this new initiative, furthermore, the government is set to incentivize the country’s “polar leap forward” by agreeing to provide financial support to “projects aimed at building icebreakers that will run through Arctic shipping routes.” By testing feasibility before these routes enter mainstream commercial use, Seoul seems to be aiming at securing early-mover advantage and establishing itself as a credible maritime actor in polar waters.

At the heart of this vision lies Busan. Already one of the world’s busiest ports, the South Korean city is being positioned as the hub for Arctic operations. The planned relocation of the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries to Busan alongside the creation of a new southern economic zone reflects a deliberate attempt to anchor national maritime strategy outside the Seoul metropolitan area. If successful, this cluster could redistribute economic weight southward, fostering new innovation centers in shipbuilding, logistics, and maritime technologies.

Equally important, Busan’s rise as an Arctic hub has geopolitical implications; it could challenge China by positioning South Korea as a preferred node in transpolar trade at a time when Beijing’s Polar Silk Road ambitions face growing scrutiny from the U.S. and its allies.

However, South Korea’s Arctic vision extends well beyond trade. Seoul has become a global leader in green shipping, aligning its industrial strengths with its climate diplomacy. The Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries’ 2025 Green Shipping Corridor Roadmap outlines an ambitious path toward net-zero maritime operations by 2050. By legislating the world’s first dedicated bill on green shipping corridors, South Korea is not only complying with global decarbonization norms but actively shaping the governance frameworks that will define the maritime energy transition.

The first tangible step will be a green containership route linking Busan and Ulsan to Seattle and Tacoma in 2027, followed by similar routes to Australia and Europe. The strategic potential of green shipping is especially pronounced in the Arctic, where black carbon emissions from traditional shipping accelerate polar ice melt thereby making decarbonized vessels a natural fit for operations.

South Korea’s ambitions also carry a security dimension. A recent joint bid by Hanwha Ocean and Hyundai Heavy Industries to supply Canada with 12 KSS-III submarines illustrates Seoul’s capacity to design polar-adapted platforms. Powered by Samsung SDI’s advanced lithium-ion batteries, these submarines can remain submerged for three weeks, an attribute directly relevant to Arctic patrols.

While aimed at Canada’s defense market, the proposal showcases South Korea’s growing ability to produce maritime technologies suitable for polar environments. As Seoul explores hydrogen-powered propulsion and hybrid systems, its defense industry may become an important enabler of sustainable Arctic operations, both commercial and naval.

The United States: From Frozen Frontier to Strategic Hinge

The United States recognizes the North Pacific Arctic as a strategic hinge connecting the Indo-Pacific to North America. Russia and China, though not formal allies, are displaying unprecedented coordination in the region. Their joint bomber patrols and naval exercises have become routine, while Beijing has poured billions into Russian Arctic energy and mineral projects. More strikingly, China has begun to operate independently in Arctic waters, sending research vessels close to Alaska. These moves signal that Moscow and Beijing see the region as a space to probe U.S. vulnerabilities.

In response, the Pentagon has combined its Northern Edge and Arctic Edge exercises under the joint purview of Indo-Pacific Command and Northern Command, emphasizing that Alaska and its Arctic waters are not peripheral but integral to global force posture. Yet the United States faces glaring capability gaps. It lags far behind Russia in icebreakers. Its communications, energy, and sensor infrastructure in the Arctic remain underdeveloped, raising questions about resilience in extreme conditions. Meanwhile, missile defense systems capable of intercepting threats over the polar approaches remain a work in progress.

These shortfalls highlight why allies like Japan and South Korea could also be indispensable Arctic partners for Washington. Both possess cutting-edge technologies and shipbuilding expertise, and both share an interest in countering Russia and China’s moves in the North Pacific and beyond.

Why Arctic Cooperation Matters

Against this backdrop, the Arctic presents an underexplored but increasingly relevant arena for modernizing the South Korea-U.S. alliance. While the idea of redeploying U.S. forces stationed on the peninsula to the North Pacific Arctic may appear to satisfy Washington’s call for greater strategic flexibility, the more realistic value lies less in large-scale force shifts and more in selective adaptation.

Embedding Arctic training and limited operational cooperation into the alliance could preserve the deterrent posture against North Korea while simultaneously providing Seoul with leverage in shaping how U.S. forces in Korea are integrated into wider regional contingencies. Such an approach would not only signal the resilience of USFK’s commitment to the peninsula but also equip South Korea with valuable expertise in extreme environments; a capability that, even if peripheral today, could become relevant should the regional security landscape evolve.

This ambition, however, is not without challenges. Arctic operations demand specialized equipment, bespoke basing, and training regimes that could divert resources away from immediate peninsula needs. The pursuit of polar know-how risks imposing opportunity costs if Seoul never elects to operate in the Arctic, while the political optics of appearing to trade Korean readiness for distant objectives may provoke domestic resistance. Given the legal and political constraints that shape non-Arctic actors’ military access to the region, moreover, the strategic return may be modest compared with investments targeted squarely at Northeast Asian contingencies.

Arctic proficiency, in other words, cannot substitute for the alliance’s more fundamental anchors: treaty commitments, operational planning, and credible deterrence on the Korean Peninsula.

Beyond force posture, the Arctic also opens opportunities in domains where Seoul’s industrial strengths align with Washington’s strategic gaps. The United States lags in modern icebreaker capacity and in scaling green maritime infrastructure, while South Korea is a world leader in advanced shipbuilding and alternative fuel technologies. Joint ventures in constructing icebreakers or pioneering Arctic-ready green shipping corridors would simultaneously enhance U.S. operational presence and allow South Korea to embed its technologies within emerging governance frameworks of Arctic navigation.

Once again, such collaboration is not without sensitivities. For one, U.S. domestic politics may favor reviving local shipbuilding while security concerns could complicate technology sharing and procurement procedures needed for the realization of any future joint venture. Still, carefully designed co-production and industrial participation clauses could mitigate these risks while delivering tangible dividends to both partners.

The geopolitical dimension is equally complex. Closer South Korea-U.S. cooperation in the Arctic would inevitably draw scrutiny from Moscow and Beijing, raising the possibility of diplomatic or economic pushback. Seoul, however, could frame engagement in this theater as strategic leverage: expanding diplomatic space, reinforcing its identity as a global maritime power, and diversifying partnerships in ways that hedge against growing uncertainty. The leverage available to Seoul is admittedly more symbolic than the tangible footholds Russia wields in Northeast Asia, and overt Arctic posturing could invite real costs. Yet if approached with restraint, Arctic cooperation can function as an additional layer of strategic depth rather than an all-or-nothing gamble.

Overall, the most promising path forward lies in pursuing targeted, dual-use, and reversible initiatives. Investments in cold-weather logistics, austere-port operations, search-and-rescue, and resilient communications facilitate interoperability for Arctic contingencies while directly enhancing readiness in Northeast Asia. Cost-sharing through public–private partnerships and joint R&D reduces the burden on any single ally. Aligning South Korean shipbuilding and green-fuel expertise with U.S. strengths in ISR creates a balanced division of labor that delivers mutual political dividends in a framework similar to the recently signed MoU between the U.S. and Japan.

By working through multilateral frameworks, prioritizing commercially led projects, and signaling transparency and restraint, Washington and Seoul can mitigate escalation risks and blunt political resistance at home and abroad and simultaneously embed Korean technology in the regulatory and governance fabric of Arctic navigation.

Conclusion

The Arctic offers a chance to reframe the South Korea-U.S. alliance. In this context, the Arctic should not be understood as a zero-sum distraction from the peninsula but as a supplementary arena where carefully crafted cooperation hedges uncertainty, enhances alliance interoperability, and converts commercial strengths into strategic resilience. Doing so will certainly not be easy due to both external and internal factors.

For instance, the U.S. and South Korea’s diverging energy strategies could become a source of friction rather than synergy. Washington’s push to advance the Alaska LNG project illustrates a vision of the Arctic as an alternative and secure source of fossil fuels. Seoul, however, is shifting away from long-term fossil fuel imports in favor of hydrogen and other sources of clean energy. Backing LNG risks locking South Korea into carbon-intensive dependencies that clash with its 2050 net-zero agenda.

Still, by aligning U.S. strategic priorities in Alaska with South Korea’s (green) shipping innovations, by combining Arctic exercises with industrial projects, and by managing risks through coordinated diplomacy, Washington and Seoul can transform their alliance into a global, multidimensional partnership. The Arctic may seem distant from the Korean Peninsula but it is precisely in this remote frontier that the future shape of the South Korea-U.S. alliance may be decided.