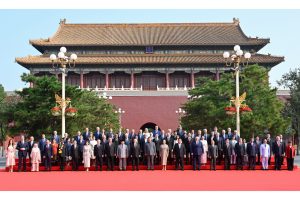

The past week offered a glimpse into a new era in China’s relations with Southeast Asia. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Tianjin on August 31–September 1 and China’s Victory Day Parade on September 3 served as a diplomatic stage – and Southeast Asian heads of state from Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar were visibly present. Their attendance underscored a deeper reality: China’s neighborhood diplomacy has reached an inflection point, one where Southeast Asia is no longer peripheral but central to Beijing’s regional strategy.

That shift rests on two pillars.

The first is governance. On April 8-9, Beijing convened the Central Conference on Work Related to Neighboring Countries, elevating “neighboring countries” to a top-tier priority in Chinese foreign policy. The meeting marked a recalibration of strategy. By institutionalizing the idea of a “community with a shared future with neighboring countries,” China moved from rhetoric to a rules-based framework embedding the neighborhood in its long-term agenda. Just days before the conference, Beijing launched the Global South Research Center to deepen policy, academic, and commercial linkages with partners including ASEAN.

The second pillar is economics. The recent U.S. tariff package on the countries of Southeast Asia – covering key exports such as electronics, textiles, and critical minerals – reinforced perceptions of Washington’s engagement as episodic, reactive, and constrained by protectionism. Beijing has responded by doubling down on connectivity, market access, and preferential rules. President Xi Jinping’s April tour of Southeast Asia paved the way for the swift conclusion of China-ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA) 3.0 negotiations in May, with signing expected by year’s end. The upgrade promises institutional support atop deeper market access for supply chains, digital trade, and industrial collaboration – the ecosystem ASEAN needs to capture the next wave of modernization.

The trade flows already tell the story. China-ASEAN trade reached $331 billion in the first four months of 2025, up 8.1 percent year-on-year, while total bilateral trade in 2024 approached $1 trillion. Sharp increases in Chinese exports to Thailand and Vietnam – even before the U.S. tariff hikes – suggest Beijing is deliberately reorienting supply chains toward the region. By contrast, the U.S. share of Chinese exports has fallen from 19 percent in 2017 to 12 percent in early 2025.

Against this backdrop, new corridors, “Twin Parks,” and industrial zones are not isolated projects but elements of a long-term diversification strategy. They represent the soft power of integration: trade and investment flowing best when matched by the circulation of students, professionals, and cultural exchanges.

The optics of the SCO summit and September 3 parade confirm the shift. ASEAN leaders did not merely attend; they lent visible support – and legitimacy – to China’s emerging narrative of global governance. Many endorsed Beijing’s Global Governance Initiative, signaling that participation now extends into the ideational domain. This week highlighted the layering of parallel governance structures, with China building platforms that sit alongside rather than replace existing institutions.

That Southeast Asian governments would be present at this moment, amid intensifying geopolitical competition and tariff disputes, shows how seriously they view China’s gravitational pull and how valuable they see embedding within its governance and economic frameworks. This is the inflection point: governance and economics are no longer parallel tracks but interwoven pillars of a coherent neighborhood strategy. Optics are not substance, but they are proof.

This new era carries implications that extend beyond East and Southeast Asia.

At the regional level, this consolidation marks a structural shift: Southeast Asia is no longer a peripheral arena but a central testbed for China’s foreign policy practice. It could sharpen divides within ASEAN between members more comfortable embedding in China’s orbit and those inclined to hedge. For outside observers, it underscores that the region’s choices will increasingly be filtered through Chinese-designed platforms and agreements.

At the global level, Southeast Asia’s embrace confirms the steady construction of a parallel rule-set anchored in economics and governance integration. For the United States, the challenge is whether to respond with credible economic engagement or continue ceding ground. Washington’s security footprint remains strong, but without a market-access strategy it risks leaving a vacuum. The EU is pushing for deeper trade integration, but its offers still pale compared to the scale and speed of China’s proposals. Japan and India present alternatives in infrastructure and supply chains, but their efforts remain selective rather than systemic.

The key takeaway is that China’s neighborhood diplomacy is no longer a margin of its foreign policy. Beijing is testing how governance, economics, and symbolism combine to produce influence in its immediate periphery.

The question is not whether Southeast Asia “chooses China.” The rules of global competition are increasingly being written in the neighborhood, and middle-sized Southeast Asian states now sit at the center of a China-led geosphere.