Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has consistently backed Donald Trump. Yet, Trump’s return for a second term as the U.S. president poses an uncomfortable dilemma: follow Washington’s China policy or preserve Hungary’s “all-weather partnership” with Beijing. For Hungary, unlike most of Central Europe, this is not just a matter of diplomacy – but one of economic survival.

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, Central and Eastern European (CEE) governments realized that being the West’s “model students” was no longer enough. Their economies needed diversification, and Beijing emerged as an attractive opportunity for regional actors. China’s arrival – through the 16+1 platform (16 broadly interpreted CEE countries and China) and the Belt and Road Initiative – appeared to offer fresh capital and a stronger role in global politics.

In the early 2010s, expectations were high. CEE states hoped China would help them reduce reliance on Western Europe, strengthening their position within the European Union. For its part, Beijing sought markets, infrastructure projects, and influence inside the EU. Yet results fell short. The 16+1 (later 17+1 with the accession of Greece) was fractured from the start, combining EU and non-EU, NATO and non-NATO states. Chinese investment lagged behind promises, and access to Chinese markets remained limited.

Still, what truly reshaped the picture was not disappointment, but pressure from Washington.

For the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the first Trump administration’s China policy carried a clear signal regarding how Washington intended to address China’s rise. In 2021, Lithuania quit the 17+1, while Poland scaled down ties to strengthen relations with Washington. Later, Latvia and Estonia also announced their withdrawal from the cooperation, which has not had a summit since 2021. As the China-U.S. rivalry grew, options for small states narrowed.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine sealed the trend: security guarantees outweighed economic opportunity. By the mid-2020s, most CEE governments had abandoned their earlier enthusiasm for Beijing.

Meanwhile, in a broader context, at the EU level, the double trend of strengthening the U.S. relationship and security dependence, as well as maintaining distance from China, became clear. The NATO summit in June 2025 reaffirmed security cooperation, while the China-EU summit the next month ended without tangible results.

Only Hungary and the non-EU member Serbia stood apart. Within NATO and the EU, Budapest faced harsh criticism for maintaining close ties with Beijing. Yet strained relations with the Biden administration insulated Hungary from pressure. Confrontation with Washington was already so deep that China was just one among many disputes.

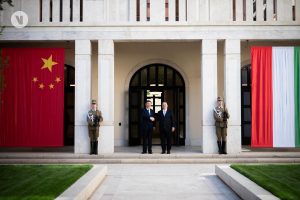

By 2024, Hungary and China had elevated ties to an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership” – Beijing’s highest label for close partners. The symbolism was backed by substance: in the past two years, Hungary has attracted more Chinese capital than Germany, France, and the United Kingdom combined.

At this point, Orban’s personal ties to Trump become crucial. A deeper alignment with Washington could force Hungary to reckon with the United States’ China policy. Yet how realistic is a reversal?

Hungary’s economy is small, open, and dependent on foreign investment. Since 1989, success has hinged on foreign capital and technology, first from Germany, the United States., and Austria and later from South Korea. The global shift to electric vehicles, however, transformed the picture. Chinese companies such as CATL and BYD now dominate battery and automotive supply chains in Hungary, while Huawei and others have embedded themselves in high-tech manufacturing.

The Ministry of National Economy ranks China as Hungary’s third-largest investor, after Germany and South Korea – but in three of the past five years, China has been number one. Crucially, Chinese investments support the very German automakers that form the backbone of Hungary’s economy. With Germany stagnating, U.S. capital retreating under the “America First” vision, and EU funds increasingly restricted, Hungary has few alternatives.

Earlier this year, Hungary’s deputy minister of foreign affairs and trade called decoupling from China a “red line.” That statement reflects a structural reality, not just diplomatic considerations. Chinese firms are now an integral part of Hungary’s economy. EU isolation and lack of alternative investors deepen the dependency.

The maximum expectation is that Orban may soften the political symbolism of Hungary’s China ties under pressure from Trump, but in substance, breaking with Beijing would mean going against Hungary’s core economic interests. That is a cost no government in Budapest is likely to bear, whatever the outcome of next year’s election.

Hungary may thus become the first U.S. ally in Europe for whom decoupling from China is not simply difficult, but virtually impossible. Hungary may foreshadow dilemmas other U.S. allies could face if Chinese capital embeds itself more deeply in their economies.