Nation-building is a long-term process that, among other elements, requires a hero who is accepted by a large section of the country’s population. In postcolonial countries, such a hero is mainly the one who led the country to independence from colonial rule.

A country’s hero, being human, cannot be perfect. In a democracy, some of his/her decisions are questioned and criticized by successive generations. Unlike a democracy, in an autocracy, a leader often uses or imposes the country’s hero to serve his/her political purpose and does not allow any serious debate on his/her role in the political history of the country.

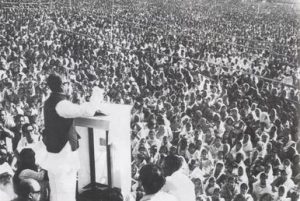

One such hero is Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who led Bangladesh in its fight for liberation against West Pakistani power elites in 1971. No matter how detractors interpret Mujib’s contribution in the country’s history, no one can deny his leadership role during the Liberation War against West Pakistan’s exploitative rule.

This year marks the 50th death anniversary of Mujib (1920-1975), who, along with most of his family members, was assassinated on August 15, 1975, by army officers who were not happy with him. Post-1975, whether under military rule or military-backed caretaker governments or Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)-led governments, other narratives of the Liberation War gained ground. During these years, the Islamists too gained political ground in Bangladesh.

Despite his heroic role in liberating Bangladesh, there are questions over how democratic Mujib’s leadership was in post-liberation Bangladesh. His government formed the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini (National Defense Force) to maintain the law and order situation in the newly liberated country, which mainly carried out atrocities against his political opponents. The Mujib government passed the Fourth Amendment to the country’s Constitution, paving the way for one-party rule and absolute power. Following the constitutional amendment in 1975, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL) was established, under which all other political parties were declared illegal and, in June 1975, most newspapers were shut down.

Under Sheikh Hasina’s prime ministerial terms (1996-2001, and 2009-2024), Mujib became the center of the country’s imagination. Hasina is Mujib’s daughter. She and her sister Rehana were the only ones in his immediate family to escape the 1975 massacre.

When protests erupted against Hasina’s rule in 2024, Mujib’s legacy was targeted. Protestors vandalized and set fire to the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Mural, the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, the statue of Themis at the Supreme Court premises, Shadhinata Sangram Bhashkarjo, the sculpture of Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin in Mymensingh, the Mujibnagar Liberation War Memorial Complex in Meherpur, and Madhusudan De Smriti Sculpture in the Dhaka University premises. Protestors also vandalized Mymensingh and Chattogram.

Six months later, in February 2025, after Hasina made an online speech from her exile in India, in which she called on her supporters to stand against the interim government, a mob, many of them affiliated with the student protesters, torched Dhanmondi-32, the residence of Mujibur Rahman. Protestors in Pabna, Chuadanga, and Rangpur also vandalized murals of Mujibur Rahman and targeted district Awami League offices, and statues and portraits associated with Awami League leaders.

In August, Nahid Islam, convener of the National Citizen Party (NCP), formed by students who led the anti-Hasina movement in 2024, wrote in a Facebook post that “through his [Mujib’s] leadership, Bangladesh was reduced to a tributary state of India, the anti-people Constitution of 1972 was imposed, and the foundations were laid for looting, political killings, and the one-party BAKSAL dictatorship.”

Any challenge to the established narrative begins with shaping the minds of young students. Post-Hasina, the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government has taken steps to create a different imagination. It set up a committee to revise the pre-existing textbooks. The aim of revision was, in the words of Rakhal Raha, who was involved in the process of making changes in the textbooks, to free students from “exaggerated, imposed history.”

In the revised textbook for 2025 titled “History of Bangladesh and World Civilization Classes Nine and Ten,” prepared by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board, the role of Mujib in the Liberation War has been sufficiently discussed. On page 202, the textbook mentions Mujib’s famous March 1971 speech, where he called on people to set up committees under the leadership of the Awami League to fight for freedom. In that speech, Mujib said: “The struggle this time is for our emancipation. The struggle this time is for our independence.”

“Major Ziaur Rahman declared the independence of Bangladesh from Kalurghat Betar Centre in Chittagong on 26th March. Then he declared independence again on 27th March on behalf of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman,” the book says on page 204.

To the chagrin of Awami League supporters, however, the book does not refer to Mujib as “Father of the Nation.” Notably, in June this year, Bangladesh’s interim government changed the 2022 law referring to him as Father of the Nation.

National heroes and symbols are not only part of shared history. In some cases, they are politically curated to communicate specific histories, burdened with warning, ambition and aspirations for the future. Understandably, then, symbols change based on a nation’s mood, changing circumstances and often owing to violent historical ruptures.

In the case of Bangladesh, Mujib’s role in the country’s liberation cannot be erased but is differently interpreted due to changed political circumstances. Attacks on Mujib’s statues and questions over his leadership in the post-Hasina era largely reflect anger against Hasina, who used his figure to justify her autocratic rule. Now the anti-Mujib forces are also using misinformation and incorrect historical facts, questioning his role in Bangladesh’s history.