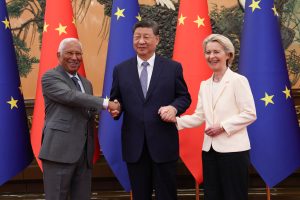

In late July, Xi Jinping hosted top EU leaders Ursula von der Leyen and Antonio Costa in Beijing for the 25th China-EU Summit. The meeting followed a months-long charm offensive, in which Beijing urged the European Union and its member states to work with China to shelve trade disputes and focus on preserving fraying global supply chains. In the months before the meeting, Beijing made an uncharacteristic show of restraint, refraining from striking back harshly against a steady drumbeat of European probes and restrictions targeting Chinese industry. Chinese officials even floated the idea of reviving the long-stalled Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, put on ice back in 2021 amid a spat over China’s treatment of minorities in Xinjiang.

Ultimately, China’s diplomatic blitz failed to impress European policymakers who wanted Beijing to concretely address their growing anxieties around overcapacity, infrastructure security, and unfair competition. Weeks out from the summit, hopes that a face-to-face meeting between Chinese and European bigwigs could achieve a breakthrough evaporated. In June, the EU walked away from a scheduled economic and trade dialogue, citing China’s lack of progress in adequately addressing the bloc’s core complaints. China subsequently canceled the second day of the China-EU Summit, in recognition of the diminishing likelihood of meaningful progress.

In the end, the summit produced little besides a boilerplate statement on climate cooperation and an EU commitment to “take proportionate, legally compliant action to protect its rightful interests” from Chinese competition.

At first blush, China’s failure to meet the EU halfway seems like a missed opportunity. With some concessions, Beijing could conceivably have enlisted Brussels as an ally in a common struggle against U.S. protectionism. Instead, the failure to get to yes on key trade issues like the EU’s tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and China’s export controls on rare earths likely means adapting to a period of protracted partial decoupling. Indeed, French President Emmanuel Macron spoke for many European policymakers when he warned of “excessive dependencies on both the U.S. and China” and an urgent need to “de-risk our economies and societies from this dual dependency” during a July visit to the United Kingdom.

But Beijing is unbothered by the failure of its European charm offensive, confident that the long-term outlook favors China. So far, EU rebalancing efforts targeting China have been modest; a far cry from the sweeping restrictions implemented by successive U.S. administrations, which have prompted a more robust Chinese response. With Brussels now having signed a punishing trade deal with Washington, Beijing has judged that European leaders are unlikely to open a second trade war front and that China’s interests are better served by dialogue than retaliation. In mid-August, China pulled yet another punch, extending its anti-subsidy probe into EU dairy by six months, indicating continued strategic patience toward Europe rather than a punitive change of tack.

Moreover, Europe’s de-risking drive has targeted some of China’s most dynamic industries, particularly clean tech, and will do little blunt their long-term competitiveness. Brussels’ imposition of anti-dumping duties of up to 35.3 percent on Chinese EVs last October was not enough to prevent Chinese automakers from achieving a 91 percent year-on-year growthh in European sales in the first half of 2025.

Likewise, EU probes into Chinese solar and wind power equipment appear to be more bark than bite. China dominates solar supply chains and although Europe is largely self-sufficient in wind energy production, the EU will need to rely on more affordable Chinese-made components in coming years or risk failing to achieve its own ambitious greening goals.

While it can’t be ruled out that the EU will adopt a more aggressive industrial policy to address its “dual dependencies,” Beijing is optimistic about its long-term odds in the EU market and sees no reason to pre-emptively reign in its domestic industry to mollify Brussels in the short-term.

Rather, Chinese policymakers will play the long game, calling for dialogue and deepening trade and investment ties with individual EU countries in an effort to outflank the bloc as a whole. China is betting that Brussels will be unable to effectively impose its hawkish line on member states. The failure of the China-EU Summit, then, was not a failure of China’s European strategy, but a reflection of Beijing’s confidence in its ability to manage ties with Europe without sacrificing anything it doesn’t want to give.