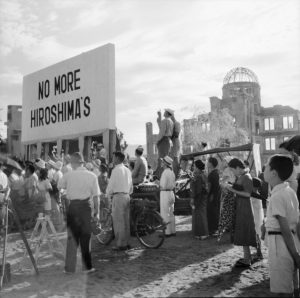

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9 respectively. According to statistics from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, as of March 31, 2025, there were 99,130 people officially designated as “hibakusha” or atomic bomb survivors left. Many of them are in their 80s or 90s and hope the next generation will carry on their work. This has injected further urgency in the mindset of many who advocate for a world without nuclear weapons.

For the Japanese government, however, its national security concerns take precedence.

According to Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui, the center of this year’s peace declaration is the phrase, ”never give up,” a quote from the late hibakusha Tsuboi Sunao, who passed away four years ago at age 96. According to NHK’s summary, “The declaration will take note of the spreading idea that nuclear weapons are needed for national defense” and “ask world leaders if they’ve ever considered the possibility that their security policies are producing international conflicts.”

The statement thus directly engages with the growing debate between the two camps of nuclear deterrence and nuclear abolition. At the center of this debate is the question of whether nuclear weapons can be instruments of protection and security, especially since that protection is hinged on the promise of a devastating retaliatory attack. Underlining these arguments are deeper, fundamental questions about whether there is a need to delegitimize nuclear weapons as vectors for security, and whether security defined on the premise of self versus the other can solve problems of insecurity at a time when the threat of use of nuclear weapons is real and immediate.

For Japan, to encourage this line of questioning would require its government to overhaul its security policy – starting with extended nuclear deterrence-based architecture. Japan depends on U.S. nuclear weapons for its security. According to the leadership, changing this and embracing a policy of global denuclearization seems “unrealistic” and “impractical.” In fact the Japanese Permanent Representative to the U.N. Conference on Disarmament said as much during the negotiations of the Treaty of Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW): “Nuclear disarmament and national security are closely linked; it is evident that disarmament will not be feasible without regard for the existing security concerns. We must not turn away our eyes from the current security situations in the international community, which are increasingly worsening.”

In its latest National Security Strategy, Japan called the present security environment “complex and severe” and, in more concrete terms than before, outlined its approach to individual or direct deterrence by proposing the creation of a “multilayered network” among like-minded countries to “strengthen deterrence.” In other words, Japan is doubling-down on deterrence, including nuclear deterrence.

Japan and the United States established the Extended Deterrence Dialogue (EDD) in 2010, and upgraded the format to ministerial talks in July 2024. In December 2024, both countries announced their Guidelines for Extended Deterrence” to “maximize deterrence and enhance measures for U.S. extended deterrence, bolstered by Japan’s defense capabilities.” This is the first indication that Japan will be involved in discussions with Washington on its possible use of nuclear weapons in response to a crisis in the region. In the most recent EDD, according to a report, Japan and the United States discussed scenarios for nuclear use in the event of a contingency, and reviewed how to coordinate and deal with issues such as managing public opinion.

Japan’s identity as a country affected by atomic bombings (hibakukoku) appears to be changing to one that is focused on deterrence under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. This might create fissures in the domestic debate on Japanese nuclear policy. In the past, this tension was not seen as a discrepancy or a contradiction, especially by its own leaders; Japan played a prominent role in the international arena arguing for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. But in the current context, where many believe the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)-based framework has failed to deliver, there are divisions between countries that have ratified the more ambitious TPNW and those that haven’t done so yet – like Japan. For the Japanese government calls to ratify the TPNW are myopic, since its sense of security might deteriorate as a result.

Under the former Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, a native of Hiroshima, Japan began to position itself as “the guardian of the NPT” and sought to play the role of bridge-builder’ to mediate between all camps: nuclear and non-nuclear states, as well as nuclear umbrella states and those who voted in favor of the TPNW). In 2022 he formed the International Group of Eminent Persons for a World without Nuclear Weapons (IGEP) to conceive of pathways toward realizing a nuclear-free world.

In a recent meeting on the sidelines of the 2025 NPT 3rd Preparatory Committee Meeting, the members of the IGEP called for “urgent actions under the three pillars: prevent nuclear war, stop the nuclear arms race and reduce proliferation risks, and work towards a constructive 2026 NPT Review Conference.” Some have suggested that Japan “work closely with the United States to systematically ‘integrate’ deterrence with arms control, nuclear nonproliferation, and multilateral disarmament diplomacy, as well as to conceive of defense diplomacy and strategy as an integrated whole.”

Eighty years since the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the current political climate is ripe for discussions on nuclear abolition. Nihon Hidankyo (Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organization) won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2024, and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) won in 2017 for its efforts in formulating the TPNW. Against these voices are security-minded policymakers, who believe that their safety in a nuclear world can only be guaranteed by a nuclear umbrella.

Some argue that these are “incommensurable nuclear worldviews.” For Japan, which sees itself as bridging both sides as both hibakukoku and a nuclear umbrella state, this debate may not be simply about bridging the gap between nuclear deterrence versus abolition, or humanitarian prohibitions regarding the use of nuclear weapons versus existing security threats. Instead, being a true bridge-builder it would entail having a conversation around security, justice, economic, social, and environmental values that underline state perceptions. That would invite a level of introspection that many might not wish to undertake.