Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be attending the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Tianjin on August 31 and is expected to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping at a time when the global stage is increasingly defined by deepening geopolitical fragmentation.

While U.S. President Donald Trump’s summits with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy have sparked some optimism about a possible peace deal between Moscow and Kyiv, global instability remains, primarily due to Trump’s tariff policies, of which India appears to be a primary target.

The recent announcement of a 50 percent tariff on Indian goods by the Trump administration has unsettled India’s growing trust in the United States as a reliable Indo-Pacific partner. At such a critical juncture, Modi’s decision to attend the SCO summit and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit to India, during which he stated that both countries should be “partners not adversaries,” signal a fresh opportunity to recalibrate China-India ties.

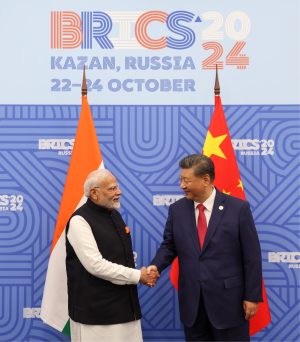

Following the deadly Galwan clashes in 2020, dialogue had come to a standstill until October 2024, when the two countries reached a significant disengagement agreement concerning the patrolling of border areas in Depsang and Demchok along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

In Tianjin, Modi will not merely be participating in another multilateral forum; he will seek to reinforce a vision of India as an autonomous power — one determined to shape, rather than be shaped by, a world order currently influenced by Trump’s assertive policies. The question is: how integral is a partnership with China (and Russia) for India in its search for strategic independence?

Engaging China: Conscious Balancing Act

India has for some time been choosing neither isolation nor complete alignment, but a third path: strategic multialignment, rooted in multipolarity and regional engagement. This basic foreign policy approach has not been impacted by the current geopolitical uncertainty. Modi’s participation in the SCO and India’s decision to improve ties with China, despite the ongoing and unsolved border tensions, support such a strategic assertion. To re-engage and rebuild ties with China also reflects a refusal to be co-opted by any singular geopolitical axis, even under intense economic pressure.

New Delhi has time and again opted for measured engagement with Beijing rather than overt hostility, even as boundary disputes have intensified over recent years. Currently, each side maintains approximately 50,000 to 60,000 troops along the LAC in eastern Ladakh, highlighting the continuing tensions despite tactical troop withdrawals.

India has always taken China seriously in its foreign policy because China’s ascent as a dominant global economic and political force makes it essential for New Delhi to maintain a functional and calibrated relationship with Beijing. Recent high-level meetings between Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Chinese leaders reflect this pragmatic recognition. While a certain level of mistrust persists, the current diplomatic thaw presents an opportunity to enhance trade and economic cooperation in areas insulated from security sensitivities.

India’s participation in the SCO, therefore, reflects not a contradiction but a conscious balancing act. For New Delhi, China is both a geopolitical rival and an unavoidable economic and regional reality. India’s efforts to play a larger role in China-dominated, non-Western multilateral forums like the SCO and BRICS have to be seen in this context. In particular, the recent BRICS expansion has provided India an opportunity to showcase its vision of a multipolar world and its pursuit of strategic autonomy, whereby it seeks to balance relations with a wide range of geopolitical players without formal alliances. India believes that its participation in both Western- and China-led forums will enhance its outreach to the Global South.

The SCO enables India to remain part of the conversations shaping the Eurasian order. Modi’s visit also comes amid China’s growing regional assertiveness, from the Belt and Road Initiative to its expanding footprint in South Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Critics may question Modi’s optics in engaging Beijing, but India’s consistent ability to maintain dialogue while standing firm on territorial integrity and economic fairness signals diplomatic maturity.

Rationale for Engagement

India’s relationship with China is deeply shaped by economic interests, particularly trade, access to rare earth elements, and technology sharing, despite ongoing tensions. Rather than isolating itself from Chinese technology and investment, India is creating firewalls around sensitive sectors while allowing mutually beneficial engagement elsewhere. This dual-track strategy supports India’s broader vision of autonomous but interconnected growth.

Trump’s attitude and tariffs are pushing the two Asian giants closer together as they prepare to open a new chapter in their relationship. A key confirmation came during Wang Yi’s recent visit, when China lifted export restrictions on fertilizers, rare earth magnets, critical minerals, and tunnel boring machines. Given that India imports nearly 90 percent of its rare earth magnets from China, such reciprocity is significant.

Trade and economic ties, though complex, have, in fact, been the stabilizing factor in China-India ties for many years. In fiscal year 2024, bilateral trade totaled $118.4 billion, with India importing $101.7 billion worth of goods from China while exporting only $16.67 billion — a stark trade imbalance, but also evidence of China’s centrality to Indian supply chains. Rare earth elements, essential for electronics, renewable energy, and defense, are another critical factor in the relationship. While India has its own rare earth reserves, it lacks advanced processing capabilities, making cooperation or indirect dependency on Chinese supply chains a strategic vulnerability. This has prompted India to seek diversification through partnerships with Australia and Canada, but cooperation with China remains an essential interim measure.

The domain of technology sharing is also seeing cautious re-engagement. Following the 2020 border clashes and subsequent bans on Chinese apps, India had significantly restricted Chinese tech access. But of late, both countries have shown interest in selective cooperation in sectors like green energy, electric vehicles, and AI research, where mutual benefit to an extent outweighs strategic rivalry. Chinese firms are also exploring indirect investment routes through Southeast Asia to continue funding Indian tech startups, reflecting a pragmatic shift in business strategy.

Beyond China: Russia, the West, and India’s Strategic Calculus

India’s outreach to China is also complemented by its steady engagement with Russia. Despite Western unease over New Delhi’s neutral stance on the Russia-Ukraine war, India has refused to compromise its long-standing strategic relationship with Moscow. That calculus remains unchanged even as Trump threatens to impose tariffs that could destabilize the India-U.S. partnership. For India, Russia serves not only as a key defense partner but also as a geopolitical counterweight to China and Pakistan. As the SCO and BRICS expand to eventually include more China-friendly nations, India’s bet is that its longstanding partnership with Russia will help balance Beijing’s growing clout within these forums. Besides, New Delhi has preferred to stay engaged in Eurasia via the Russia-India-China (RIC) trilateral, which has been the driving force behind the birth of the BRICS as well as the inclusion of India in the SCO.

Russia is now pushing to revive the RIC trilateral mechanism, in hiatus since the Galwan clashes. The rationale for the RIC, dating back over three decades, is to reshape the global order in favor of emerging economies by bringing together the three largest Eurasian powers and emerging economies outside the Western bloc. China supports a revival of the RIC while India has been cautiously open about this “consultative format,” hedging its bets for the time being. This rekindling of interest in the RIC comes at a critical juncture when all three nations are facing varying degrees of pressure from the West.

The joint communique issued at the last RIC meeting in 2021 expressed solidarity and belief in “a multipolar and rebalanced world.” When read in today’s context of Trump’s tariff policy, the language on the need for a “transparent, open, inclusive and non-discriminatory multilateral trading system” is particularly interesting.

Though many Western nations have downgraded ties with Moscow following the Ukraine war, India has held firm to its principle of strategic autonomy. Modi’s consistent message — that “this is not an era of war” — captures New Delhi’s insistence on diplomacy over isolation, even as India has increased energy imports from Russia and maintained defense cooperation.

Contrary to the perception that India’s balancing act might alienate the West, ties with the United States, European Union, Japan, and Australia have only deepened in the last decade. From Quad cooperation on the Indo-Pacific to defense agreements with Washington and a free trade agreement with the United Kingdom, India is investing heavily in strategic partnerships with these actors. These alignments are issue-based and interest-driven, particularly in balancing out China’s regional dominance and advancing India’s economic and technological cooperation, even if there may be occasional setbacks.

As New Delhi keeps its options open, the Tianjin meeting should also be read as a signal to Washington: India will continue to collaborate where interests converge, but it will not fall into a “containment” strategy against China that undermines its regional priorities or strategic flexibility. In summary, India’s current foreign policy posture is a clear-eyed assessment of global realities, and a strategic bet on multipolarity (or reformed multilateralism) as the most stable and equitable global architecture in a time of flux.

Whether engaging China bilaterally and multilaterally, including at the SCO, maintaining strategic depth with Russia, or advancing Indo-Pacific cooperation with the West, New Delhi is guided by a sovereign calculus of interests and influence. Modi’s appearance in Tianjin is emblematic of this vision. In attending a forum led by its foremost rival, India is ensuring it remains an indispensable actor in all theaters of global governance.

This piece originally appeared on South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center’s online policy platform, and has been republished with permission from the editors.