This piece is part of a series of articles covering the medieval and early modern great powers of each of Asia’s regions: East Asia, Central and North Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and West Asia (the Middle East). Each article discusses the great power dynamics of the main powers within that particular region as well as how the main powers of each region interacted with those of other regions. To view the full series so far, click here.

South Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, sits in the middle of Asia, athwart the land and sea routes between West and Central Asia on one hand and Southeast and East Asia on the other hand. India had the world’s largest economy, accounting for between a fourth and a third of the world’s wealth, by the start of the common era, and continuing for 15 centuries. In 1000 CE, at the heart of the medieval era, the Indian subcontinent was more populous than China, and its influence and culture spread far and wide over Asia.

In his book, “The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World,” historian William Dalrymple described how India was at the center of an “Indosphere,” wherein “the rest of Asia was the willing and even eager recipient of a startlingly comprehensive mass transfer of Indian soft power, in religion [Hinduism, Buddhism], art, music, dance, textiles, technology, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, mythology, language [Sanskrit] and literature.” Dalrymple went on to note that the centrality of India’s economy and culture in Asian history has since been obscured by an overly Sinocentric view of history, which confines India to the role of an “almost passive observer of, and a lucky recipient of largesse from” the main current of history, the interaction between the West and China via the so-called “Silk Road.”

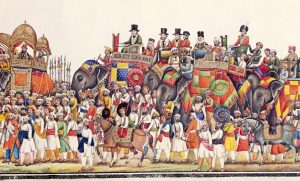

In reality, most of Rome’s overseas trade was with India, and the volume of commerce across the Indian Ocean, far exceeded the overland Silk Road. The Indosphere was much larger and more influential than the much smaller Sinosphere. It was India that Christopher Columbus sought to reach, and it was India that the British viewed as crucial to their empire: “as long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop straight away to a third-rate Power.”

It is true that the political unity and bureaucratic efficiency of China gave it geopolitical weight and strategic coherence that has been unmatched by most Indian states; it is also true that India has been on the receiving end of foreign colonialism to a greater extent than China. But in general, India’s culture and economy have been more influential in world history, and its interaction with the Islamic and Western worlds has only served to spread its influence even wider.

Dalrymple attributed this lopsided understanding of history to Chinese branding and India’s political fragmentation, though the latter should also be seen as a sign of dynamism, because it facilitated local development and autonomy, even if it made geopolitical projection more difficult. Even today, modern India sometimes seems so absorbed with managing domestic sociopolitical issues — negotiating between and balancing the interests of different castes, regions, ethnic, and linguistic groups — that foreign policy and geopolitics seem to be secondary concerns. This, along with India’s physical geography, contribute to a sense that India’s strategic perspective is often insular.

Place in the World

But Indians did have a sense of the world and their place in it. The Mughals maintained diplomatic relations with the Chinese, Persians, Ottomans, and various European nations. According to Nana Fadnavis, a Maratha minister in the 18th century, the world’s five great powers were the Qing Empire of China, the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, France, and of course, the Maratha Empire of India.

Although the ancient Sanskrit text, the Arthashastra, envisions a centralized bureaucratic state, in practice, most Indian polities from the Gupta Empire (220 CE-550 CE) onwards were decentralized, with local leaders, caste-based groups, and others managing local affairs. According to Indian historian Aniruddh Kanisetti, merchant guilds and nadu assemblies in villages of the Chola Empire of Tamil Nadu, which flourished between 848-1279 CE, raised or denied kings revenue and initiated the construction of temples, irrigation projects, and other infrastructure. This pattern of rule persisted for over a thousand years, well into the Islamic period. Douglas Streusand, a professor of international relations, noted in his book “Islamic Gunpowder Empires” that the Mughal government “floated” above provincial society: it “did not interact directly with the general population but collected revenue through local intermediaries (zamindars).”

Any major Indian empire, even one that controlled a portion of the subcontinent, would be quite dynamic and powerful, second only to whichever Chinese dynasty was ruling at that time. Geopolitical observers across medieval Asia would describe the largest Indian empire of their day as one of the world’s great powers. Even if Indian kings did not control the entire subcontinent and were concerned with domestic issues, by concentrating so much wealth and population, they were able to impact world events.

Mountainous Barriers

One of the defining features of the subcontinent’s geopolitical posture are the mountain ranges separating it from the rest of Asia, particularly the Himalayas and Hindu Kush mountains. George Nathaniel Curzon, the British viceroy of India between 1899 and 1905, described these mountainous barriers as some of the “most durable,” and noted that “the labor in crossing a mountain range is commonly great, particularly for armies…”

The Himalayas, the world’s highest mountain range, rise sharply from the subcontinent. They are over 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) long and up to 400 kilometers (250 miles) wide. According to historians Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot, writing in “India Before Europe,” this has “largely sealed off access to the subcontinent from the north.” Indeed, barring some skirmishing between local Himalayan states, the Himalayan frontier did not feature prominently in Indian geopolitical history before the establishment of the modern Sino-Indian border.

The subcontinent’s mountain ranges, together with a string of deserts in its west and sparsely populated swamps, hills, and rainforests to the east of Bengal, render the region almost an island. It has some of the best natural frontiers imaginable. Much of southern India forms a large peninsular plateau, the Deccan, which is surrounded by the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. Seas, mountains, and deserts, while serving as barriers to conquest, were not impenetrable, and also served as highways for commerce and the spread of culture. In particular, peninsular India was the hub of Indian Ocean trade, propelled by using monsoon winds to navigate large distances. India thus has a geographic and cultural coherence that was noted by both Indian and non-Indian observers. Despite its political fragmentation, India was a term that always referred to a concrete place, variously known as India, Bharat, Hindustan, and Jambudvipa.

While mountains had defense advantages, they also made it difficult for Indian states to project power outward into the rest of Asia. Furthermore, there was generally little desire to do so, as the effort and cost were not worth the return of holding onto large portions of Central Asia or Tibet. Conversely, most invasions of the subcontinent came from the direction of the lower of the two major mountain ranges abutting the subcontinent — the Hindu Kush — because it is easier for an army to descend from high ground into a plain than for the opposite to occur.

The wealth and population of the subcontinent, moreover, made India a frequent target of invasions from Central and Western Asia. Curzon suggested that an Indian state could avoid this situation by controlling as much of a mountain range as possible, so as to place “both the entrance and the exit of the [mountain] passes in the hands of the defending power.” This logic led to the forward school of the British in pushing India’s boundaries outward to the Durand and McMahon Lines, which today form the borders between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and India and China.

Another key geopolitical characteristic of South Asia — of utmost importance to premodern polities — was its enormous population. The first Mughal emperor, Babur, observed that India had “unnumbered and endless workmen of every kind.” The historically famed wealth of India is due more to this than any other factor. With this large labor pool, India was able to produce much to export, whether cotton or gold or spices, all of which are found elsewhere. India’s large population can be attributed to its climate and monsoon season, which allows multiple harvests in a year and several staple crops, including rice and wheat. A large population is also a large tax base and reservoir of military manpower, a fact that both the Mughal and British empires found useful in projecting their might globally.

Front view of Gwalior Fort, in present day Madhya Pradesh, India. Credit: Wikipedia/Anuppyr007

Medieval India

As India entered what historians call the medieval period in the sixth century CE, the Gupta Empire, which had ruled the north Indian plains for three centuries, was disintegrating, often in the face of attacks from Central Asia by the Huna — people related to the Huns who fought the Roman Empire. Although the Huna were defeated, they set up many statelets in Afghanistan and western India.

Much of India fragmented into numerous regional kingdoms after the disintegration of the Gupta Empire. Historians Asher and Talbot described this as a “normal course of affairs in such a large and diverse area,” one featuring different ecologies, cultures, and subregions. States often sought to expand their power not through direct conquest — taking and holding too much territory was difficult — but through the mandala theory, in which states projected power outward through circles of tributaries. But India’s state system was unable to achieve a stable balance of power, as in Europe, because of the occasional appearance of large empires that wiped away regional entities and sought to unite the subcontinent.

It would be difficult to describe the course of events in medieval India in a single essay; India’s innumerable kingdoms had different geopolitical strategies and imperatives. Some, like the Cholas of Tamil Nadu, developed significant overseas influence that was rare among premodern Asian polities, projecting power into Southeast Asia. However, one overarching pattern emerges: India’s dominant states were concentrated in three zones, and each of these contained a leading empire of its day that tried to achieve dominance over the rest in order to become the subcontinent’s paramount power. On top of this, invaders — usually Turkic — from the steppes of Central Asia or Persia often entered the fray by way of Afghanistan, establishing states in western or northern India that sought to expand over the rest of the subcontinent.

The first of these three zones is the western part of the Deccan plateau, a mountainous region comprising Maharashtra and Karnataka. A succession of powerful empires dominated the Deccan and expanded toward the populous Gangetic plain of north India from here: the Vakatakas (220-510 CE), the Chalukyas of Badami (543-753 CE), the Rashtrakutas (753-982 CE), the Chalukyas of Kalyani (957-1184 CE), Vijayanagara (1336–1646 CE), and the Marathas (1674-1818 CE). Similar to Afghanistan, the mountainous terrain of this region made it difficult to conquer, and contributed to a local culture of hardy warriors. By the time of the Marathas, the people of this region were known for their guerrilla techniques and use of swift light cavalry, according to historian Richard M. Eaton in “India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765.”

The second of these three zones is the densely populated eastern Gangetic plain, which corresponds to the regions of Bengal and Bihar. Formerly the heartland of the powerful classical Maurya and Gupta empires, the overall might of this region declined during the medieval era, though it was home to extraordinarily wealthy dynasties. These states tended to be less successful than those in other parts of India in projecting power. Prominent empires from this region include the Palas (750-1161 CE) and the Bengal Sultanate (1352-1576 CE). The most successful use of this region in establishing a subcontinental empire, however, was by the British, who established their control over Bengal after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Subsequently, the British were able to marshal the resources of Bengal to expand throughout India.

The third zone is the western part of the Ganges valley — which includes most of modern Uttar Pradesh and Haryana — and the surrounding hilly and arid regions in Rajasthan and the Malwa plateau of Madhya Pradesh. This has been the dominant region throughout much of the subcontinent’s history, and became even prominent during the medieval era. Much of the time, it has been the base of power of dynasties that invaded India from Central Asia, but its proximity to the borderlands of the subcontinent also engendered the formation of local mighty warrior peoples, ranging from the Rajputs to the Sikhs. It was from this area that the Rajput warrior clans, who dominated much of India for centuries, originated; Hindi, India’s most prominent language, comes from here; the heartland of Mughal power was here.

This zone largely overlaps with the Aryavarta of the ancient Vedic period, which stretched from the Himalayas to the Vindhyas of central India and encompassed the doab, the region between the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. While the densely populated doab has been a source of power for many empires, many of the region’s ruling groups originated in the hilly regions abutting it, from Rajasthan, Malwa, or Afghanistan. Prominent states in this region include the Pratiharas (730-1036 CE), the numerous Rajput kingdoms that originated as tributaries of the Pratihara state, such as the Chauhans and Sisodias of medieval Rajasthan, the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526 CE), and the Mughal Empire (1526-1858 CE).

The rivalry between the empires of the three zones for supremacy over the subcontinent is epitomized by the tripartite struggle between the Pratiharas, Palas, and Rashtrakutas for the central Ganges valley and the city of Kannauj in the 8th and 9th centuries CE. The Pratiharas emerged victorious in this struggle, but power continued to vacillate between the three polities, especially between the Rashtrakutas and the Pratiharas. While much of the energy spent by these subcontinental powers was over India, they were also able to pay attention to threats from outside South Asia. Both the Pratiharas and Rashtrakutas defeated the Arabs, who had established themselves in Sindh, checking Muslim expansion into India for centuries. At the end of the 12th century, the Ghorid Empire, based in modern Afghanistan, overran much of northern India after defeating Rajput dynasties.

Delhi Sultanate

Subsequently, the Delhi Sultanate, ruled by various dynasties of Afghan or Turkic origin, was founded in 1206 CE. The Delhi Sultanate briefly expanded over much of the subcontinent, but faced the familiar problem of being unable to control all of India, with breakaway sultanates appearing in Gujarat, Malwa, Bengal, and the northern Deccan’s Bahmani Sultanate (1347-1527 CE). It also had to contend with powerful Hindu rivals in Rajasthan and Vijayanagara in southern India.

Eventually, the Mughal Empire replaced the Delhi Sultanate in 1526 CE. Founded by Babur, the ruler of Kabul and a scion of the Turko-Mongol Timurid dynasty, the Mughals spent much of their heyday — over two centuries — trying to establish their rule over all of India. Like previous dynasties, they had to particularly contend with powers based in eastern India and the Deccan.

Babur described Vijayanagara and Bengal as among the most powerful and wealthy kingdoms in Hindustan. In eastern India, these included the Bengal Sultanate, the Sur Empire (1540-1556 CE), and the later breakaway nawabs of Bengal, who were eventually subdued by the British. The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (ruled 1658-1707 CE) spent most of his reign trying to conquer the Deccan region, which included successor states of the Bahmani Sultanate and the nascent Maratha polity. Ultimately, they were unable to do so, and the Marathas dominated much of India for the 18th century.

While most subcontinental empires during this period, such as the Mughals, were focused on dominating South Asia and fighting other powers in the region, they kept an eye on their geopolitical position vis-à-vis the rest of Asia, even if this was not prioritized. For example, the Mughals sought to dominate the approaches to the subcontinent via Afghanistan, sending armies to Balkh (Bactria) to fight the Uzbeks and to Kandahar, which frequently changed hands between the Mughals and Safavid Persians. Both the Cholas and Marathas recognized the importance of controlling the seas neighboring India and guarding the approaches to the subcontinent.

Yet the fact remains that due to the geographic and demographic features of the subcontinent, Indian powers often perceived it to be fruitless and unnecessary to expand too far beyond the region’s boundaries. It was enough to dominate the subcontinent to become a major power in the world. By doing so, they would automatically control over a quarter of the world’s population and wealth. Anything more would have been overreach.

As the medieval period transitioned into the early modern and then modern eras, the British Raj came to rule over most of India, either directly or indirectly. This era had its ups and downs, but from a geopolitical perspective, the British left India a favorable strategic legacy.

Modern India is a coherent nation-state that does not have to expend its resources and energies fighting other regional states, although an echo of this tradition exists in the Indo-Pakistani rivalry today. Modern India, as a united state, has natural boundaries in most places, a large demographic and economic base, and the ability to patrol and protect both the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean. India is in a good position to project power and influence other regions in Asia and take its place as one of the great powers of the world.