In the first half of 2025, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed more than a thousand attacks, with over 300 attacks in July alone, as it intensified operations across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and southern Punjab, Pakistan. Yet beyond the rising body count, a more subtle evolution is underway. Once defined as a religious militant organization fighting to impose Islamic law or Shariah, the TTP now frames its struggle as a broader political and ethnic battle against the Pakistani state, deploying a coordinated a propaganda campaign to position itself as the guardian of the Pashtun nation, invoking tribal honor, civilian suffering, and ethnic identity.

The Narrative Shift: From Religious Vanguard to Tribal Guardian

The TTP emerged in 2007 from a coalition of militant factions in Pakistan’s tribal areas, combining a hardline Deobandi ideology with alliances to al-Qaida and the Afghan Taliban. It rapidly became one of Pakistan’s most lethal insurgent groups. Framing its campaign as defensive jihad, the TTP embedded Islamist goals at the core of its insurgency, carrying out attacks against security forces, civilians, and minorities.

From 2014, however, sustained Pakistani military operations, U.S. drone strikes, and internal divisions severely weakened the group, reducing its attacks to a historic low by 2018. Beginning in 2019, signs of the TTP’s revival began to emerge through an increased attack tempo, merger announcements with other militant factions, and intensified propaganda. This slow revival accelerated into a violent resurgence post-2021, enabled by a more regionally permissive environment linked to the Afghan Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan.

Historically, the TTP’s propaganda leaned heavily into religious justifications of its goals and operations, with the group’s founding charter in 2007 explicitly stating three central missions: enforcement of Shariah, establishing a unified front against U.S.-led coalition forces in Afghanistan, and conducting defensive jihad against Pakistani security forces. This religious militancy manifested in concrete actions, such as a 29-page fatwa issued against Pakistani media in 2014.

Recently, the group’s ideological playbook has shifted. Religion remains central, but the TTP has increasingly woven ethnic identity and localized grievances into its messaging, an adaptation seemingly designed to exploit societal discontent and sustain its relevance amid shifting conflict dynamics.

Generally, religious fundamentalism aims to create a faith-based community that transcends ethnic or territorial divisions, while ethnonationalism seeks to defend the political and material interests of a specific ethnic group rooted in notions of common blood and territory. Though often seen as incompatible, the two can hybridize into powerful ideological frameworks, as demonstrated by the Afghan Taliban’s fusion of fundamentalist Islam with Pashtun ethnonationalism. The TTP’s current rebranding reflects a similar blending, as it layers Islamist goals onto narratives of Pashtun solidarity.

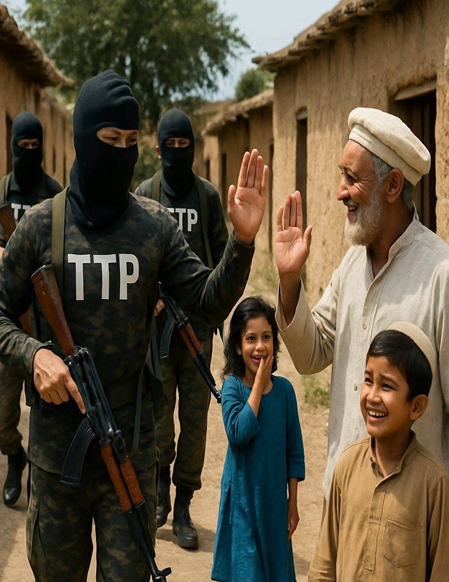

In this TTP propaganda image, a TTP militant commander, Ilyas Malang Bacha, addresses locals in Bajaur during Eid celebrations. Source: Telegram.

A Rational Pivot to Ethnic Grievances and Identity Narratives?

Three converging pressures have pushed the TTP toward its ethnonationalist rebranding: theological delegitimization by the Pakistani state and religious figures, recruitment competition (and criticism) from rival militant groups, and the rising salience of ethnic grievances in the region’s broader landscape.

States often seek to erode militant legitimacy by recasting them as religious deviants; In 2024, Pakistan’s Ministry of Interior formally directed that the TTP be referred to as “Fitna al-Khawarij.” This rhetorical change aimed to frame the group as theological deviants, drawing on the historical Islamic term Khawarij for extremists who reject legitimate authority. Well known pro-state scholars like Mufti Taqi Usmani and Mufti Abdul Rahim have also boosted the state’s anti-TTP campaign by criticizing the TTP’s narratives.

Rivalries and competition with other military groups have also forced the TTP to adapt. Post-2021, the TTP faced renewed competition from the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), which aggressively expanded its recruitment through multilingual propaganda campaigns, while also exploiting the TTP’s association with the Afghan Taliban to position itself as the purer alternative.

Finally, ethnic politics has grown in salience across Pakistan’s militant landscape, illustrated by the rise of Baloch insurgent attacks on security forces and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor targets. In this competitive space, ethnic slogans perhaps travel further than religious ones, incentivizing the TTP to fuse Islamist rhetoric with Pashtun nationalist narratives.

Cultivating Societal Legitimacy

To broaden its appeal, the TTP has sought to recast itself as a representative of Pashtun society through outreach to tribal communities, reframing violence in ethnic terms, and modernizing its propaganda apparatus.

Seeking to bolster its connection with Pashtun communities, the TTP has increasingly portrayed itself as tolerant of political voices critical of its agenda, framing such gestures as part of a shared struggle against state oppression. For instance, after the targeted killing of Molana Khan Zeb, a peace activist and outspoken critic of both the TTP and rising militancy in Bajaur, the group not only condemned the attack but also published a tribute in the July edition of its Pashto magazine, Mujallah Taliban. The TTP used Khan Zeb’s killing to urge Pashtun unity against what it portrays as state-engineered chaos.

Propaganda videos like Jihad ka Musafir showed leaders meeting locals in Bannu, while commander Ilyas Malang Bacha addressed crowds in Bajaur during Eid celebrations. Other materials depict militants alongside Afghan fighters from Nuristan, framing the conflict as a cross-border Pashtun resistance rooted in grievances over the Durand Line and displacement from military operations. Further, press releases and speeches refer to TTP militants as the “sons of the soil,” with visuals showing fighters attending jirgas, meeting elders, and seeking tribal mediation for the release of captured locals and security personnel.

Yet these symbolic gestures of inclusion mask a stark contradiction: the group continues to target tribal leaders, such as Allah Noor, Bhittani leader Inamullah Khan, and Dawar chief Malik Muhammad Rehman.

In its targeted killings of Aman Lashkar and peace committee members in Bannu, Laki Marwat, and DG Khan, the TTP framed violence as punishment for betraying Pashtun interests, branding victims as “spies.” By replacing religious labels like “apostate” with the politically charged language of betrayal and espionage, the TTP recasts its violence as defense of a collective Pashtun cause.

In areas with tribal support, TTP has worked through traditional mechanisms, detaining officials but releasing them after jirga mediation, presenting itself as part of the tribal justice system. This blending of ethnic and religious cues is also evident in the TTP’s repeated invocation of the 2004 Wana Operation Fatwa, which it claims was signed by 500 scholars, including the influential Mufti Nizam Uddin Shamzai.

Through a tech-savvy propaganda apparatus, and under Muneeb Jutt’s leadership, the TTP has placed tribal grievances and the Pashtun identity at the center of its cause. The TTP’s extensive multimedia digital footprint blends traditional messaging with modern technology, using AI-generated posters on X and Telegram, with visual depictions of alleged military atrocities, destroyed homes, and symbolic imagery of Pashtun resilience.

Additionally, the TTP’s media strategy employs popular jihadi nasheeds as soundtracks coupled with traditional visuals from battlefields, using titles like Shaheen Jawan, Rasm-e-Muhabbat, and Markay hain Tez Tar, deliberately named after popular nasheeds with thousands of YouTube views.

In public releases addressing Swat and North Waziristan locals, the TTP has blamed the military for indiscriminate violence, citing mortar attacks in Tank and Khyber, while also linking natural disasters such as the Swat floods to governance failure.

An AI-generated image used in TTP propaganda, in which TTP militants engage with society members. Source: Telegram

Risks of Ethnicizing the Conflict

The TTP’s self-portrayal as a defender of Pashtun identity alongside a jihad mission carries the potential to deepen societal rifts and fragile bonds between communities and the state. Central to this narrative is the invocation of historical Pashtun resistance figures, like Faqir Ippi and Haji Sahib of Turangzai, and the portrayal of the Durand Line as a colonial remnant. Such narratives place tribal groups, especially those that historically cooperated with the state through Aman Lashkars or peace committees, in a precarious position. The suspension of 42 Orakzai police officials for refusing anti-terror operations, which the TTP praised, illustrates the coercive pressures at play, reinforced by intimidation campaigns, and selective outreach, and conditional prisoner releases.

At the same time, the TTP’s ethnic framing is not confined to any one province. This is evident in the TTP’s glorification of militants like Habib ur Rehman (Abdul Basir Shami), a Punjabi from a conservative Salafi family who allegedly traveled to Syria prior. The TTP’s recruitment drives appear to have expanded into southern Punjab, particularly DG Khan and Mianwali, targeting Siraikis and ethnic Balochs, while continuing to exploit Baloch nationalist grievances. The portrayal of fallen militants as honorable defenders of both the ummah and the tribal nation is clearly intended to inspire sympathizers far beyond the tribal belt.

Policy Implications

The TTP’s rebranding underscores that kinetic operations alone will not resolve Pakistan’s militancy and terrorism problem. While military pressure can disrupt cells and prevent large-scale attacks, as seen in operations in Hangu, North Waziristan, Bajaur and Orakzai, it does little to blunt the group’s evolving narratives. At the same time, evidence of operational collusion with Baloch militants and the use of advanced equipment like sniper guns with thermal sights, assault rifles and magnetic IEDs suggest the TTP’s evolving capabilities. Countering this evolution will require an integrated approach.

Pakistan should pursue targeted counter-narratives that address both religious and ethnic dimensions of TTP propaganda, particularly responding to the TTP’s invocation of the “Wana Operation Fatwa.” Authorities should both monitor and disrupt AI-driven and social media campaigns that amplify the TTP’s image as a local protector, particularly on platforms where they maintain pseudo accounts and coordinate with militants like Jamatul Ahrar, whose Qari Shakeel group recently joined the TTP.

At the same time, political engagement with tribal communities is necessary to restore trust and address legitimate grievances about incidents like the Janikhel drone strike, and Tank and Khyber mortar deaths. Pakistan should institute transparent incident-review mechanisms for civilian harm, such as publicly accessible forums or jirga-style hearings where the state acknowledges accidental killings, explains investigative findings, and offers restitution – undercutting the TTP’s monopoly on grievance narratives. Localized accountability forums in high-risk districts can bring together civil administrators, security forces, and community representatives to address allegations of abuse or neglect before they are weaponized in militant propaganda.

Finally, the state should strengthen provincial autonomy mechanisms to reduce perceptions of interference in provincial security matters, ensuring that law enforcement reforms and force restructurings are driven by local political actors

Unless Pakistan can respond to the hybrid threat – part insurgency, part perception war – the TTP’s self-rebranding as the defender of the Pashtun nation could entrench its influence, and risk a broader ethnicized insurgency.