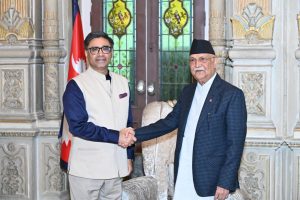

For 14 months since becoming the prime minister of Nepal last July, K.P. Sharma Oli kept knocking on India’s door. This September, the door will finally swing open to let him in.

Oli knew his premiership would remain shaky without New Delhi’s backing. India, which has deep trade and cultural ties with landlocked Nepal, has traditionally been a big determinant of the longevity of governments in Kathmandu.

Yet for a long time, India rebuffed Oli’s pleas for a formal invitation. They had had enough of a man who, in their view, had repeatedly undercut vital Indian interests and cozied up to China. As a result, the much sought-after official invite to India remained elusive to the Nepali prime minister.

When Oli’s formal India trip was announced earlier this month, it, therefore, came as a surprise.

At the invitation of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Oli is scheduled to visit India on a two-day official trip on September 16. Before that, he will be in China to attend the summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), where he is expected to meet China’s President Xi Jinping and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin — as well as Modi. There are even rumors of a trilateral between Xi, Modi, and Oli.

Separately, Oli’s PR team is already painting the impending India trip as a major success. Or that was the case before August 19.

On that day, India and China agreed to open three traditional border routes, including one that runs via Lipulekh pass, which lies in the Nepal-India-China trijunction. Though currently under India’s control, Nepal has traditionally asserted its claim over Lipulekh. With India and China declaring the pass open for business without Nepal’s consent, Oli will now be under pressure to take up the matter forcefully with both countries. This potentially explosive issue will now hang over Oli’s twin trips.

But, to start with, why did India agree to see Oli after ignoring him for so long?

When I sought answers with some analysts, both in India and Nepal, there were a few reasons they repeatedly brought up.

First, the upcoming state election in Bihar is a big part of Modi’s Oli calculus. This time, far from the power corridors of New Delhi, Modi is meeting Oli in Bihar’s Bodh Gaya, the place where Lord Buddha attained enlightenment. People in the Tarai-Madhesh belt of Nepal enjoy close roti-beti (literally bread-daughter, a metaphor for the warm bilateral ties) relations with those across the border in India, including in Bihar, which shares over 700 km of border with Nepal. Modi hopes hosting a Nepali prime minister on the eve of an election translates into a sizable number of Bihari votes for the Bharatiya Janata Party.

Second, India is desperately searching for friends in light of its poor relations with countries near and far. Currently, its relations with Pakistan and Bangladesh have hit rock bottom, while ties with the Maldives and Sri Lanka, although better, are not without problems. The deterioration in ties with the U.S. has put further pressure on New Delhi. So, India’s outreach to Oli is part of its effort to rebuild international friendships and prevent further isolation.

As one Chinese scholar of South Asia told this author earlier this week, “Strained U.S.-India ties might even make India more open to China’s engagement in the region, including in Nepal.” The Bihar election is thus the proximate cause for Oli’s visit in the larger backdrop of India’s growing international isolation.

Third, it had also become difficult for New Delhi to continue to brush aside repeated requests from Kathmandu for a formal visit. India was not in favor of the Oli government, largely because of the tense history between them. But then it realized that the balance of power in Kathmandu is such that it would also be hard to remove Oli easily. So it chose rapprochement instead.

Perhaps New Delhi really is rethinking its approach to South Asia and Nepal amid the fast-changing global politics. But old suspicions about Oli linger. This is why, while hosting him, Modi is unlikely to enter into controversial topics like the Eminent Persons Group (EPG) report on the reevaluation of the India-Nepal ties, or the resolution of age-old border disputes.

Yet there could be some progress on specific projects like Pancheswor, the long-delayed water and electricity sharing mega-project between the two countries. Oli will also broach the topic of an additional air route in order to operationalize its new airports in Pokhara and Bhairahawa. Progress is also expected on the long-delayed extradition treaty or having some version of it.

After being in India’s bad books for so long, there is a chance for Oli to regain New Delhi’s confidence. It won’t be easy, though. Nepali communist parties, including Oli’s CPN-UML, have traditionally been suspicious of “expansionist” India. A close embrace of Modi will fuel some discomfort in the party rank and file — and now there is Lipulekh.

Curiously, back in 2015, the scheduled India visit of the then-Nepali Prime Minister Sushil Koirala had to be canceled when India and China had signed a similar agreement to open trade through Lipulekh. Nepal had strongly objected and India did not respond kindly. This time, too, if Oli does not handle the emotionally charged issue of Lipulekh for Nepalis with the sensitivity it deserves, his budding engagement could again hit a roadblock.