“You know that whole place used to be sugarcane,” says Quazi, my cab driver from Bangladesh, who has lived in Saipan, the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands for over 35 years. He’s driving me to the small airport; in just 15 minutes, I’ll be landing on Tinian, the topic of our discussion.

“But before all that, it was a boomtown during the Japanese era,” Quazi adds.

Map via Wikimedia Commons

Tinian, today a sleepy speck in the Pacific, was once a bustling cog in Japan’s imperial machine. From 1914 to 1944, the island was under Japanese administration as part of the South Seas Mandate. It became an agricultural powerhouse, thanks to the Nanyo Kohatsu Kabushiki Kaisha, the South Seas Development Company. They brought in thousands of settlers – Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean – to work the cane fields and live in rigid, plantation-style communities.

The island had five key settlements before the war: Sunharon (now San Jose), Marpo, Churo, Asiga, and Kahi, though many were more plantation clusters than formal villages. At its peak, Tinian housed around 18,000–20,000 people, nearly all drawn by the lure or pressure of the sugar industry.

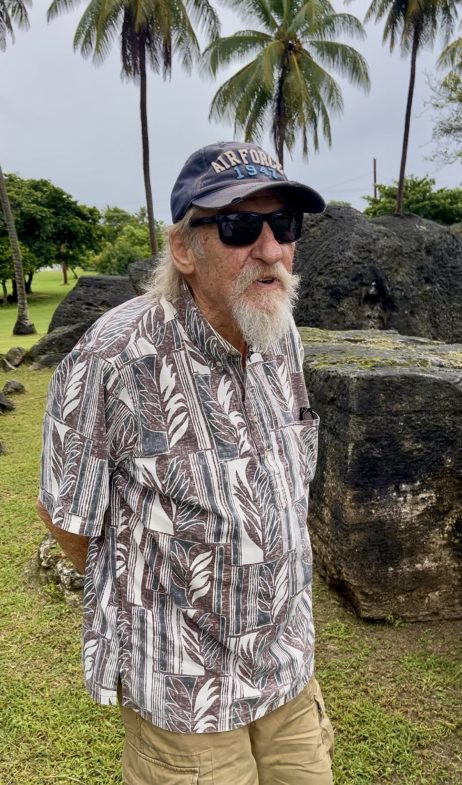

The remnants of a pre-war Japanese village shrine on Tianian. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.

“There was a real community here,” says Pedro, a Chamorro elder I meet at a small church garden overlooking the sea, “They had an elementary school, a health clinic, even an agricultural school.”

Tinian, during its time under Japanese administration, was a fully functioning plantation society, centered almost entirely around sugarcane.

“Sugarcane only produces one crop a year,” Pedro explains. “It’s usually planted around February and harvested in October or November. And when that harvest came in, it was a big deal. Everyone got paid at the same time, one paycheck a year.”

That single payday set the rhythm of island life. “After the harvest, they’d throw a huge, island-wide party,” he says. “People would finally have cash in hand.”

Then the war came.

Don Farrell, a noted historian of the Northern Mariana Islands. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.

“Between July 24 and August 1, 1944, U.S. Marines of the 2nd and 4th Divisions landed under the shadow of naval artillery and swarming bombers. They faced some 9,000 Japanese troops defending an island of caves, tunnels, and desperation,” says Don Farrell, a leading historian of the Northern Mariana Islands and the author of works like “Atomic Bomb Island” and “Tinian and the Bomb,” which detail the island’s pivotal role in World War II.

In less than two weeks, it was over. The Japanese defenders were killed almost to the last man. In their place came the U.S. military, en masse.

“Fifteen thousand Navy Seabees laid concrete over cane fields. North Field, built in months, soon became the largest airbase in the world,” Farrell explained.

Its four 8,500-foot runways capable of launching waves of B-29 Superfortresses. By 1945, 50,000 American personnel were stationed on this once-remote island.

Tinian became the final stage of the Manhattan Project. Here, under armed guard and surrounded by tropical quiet, the atomic bombs were prepared. “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” were loaded into the Enola Gay and Bockscar, respectively, in bomb pits still visible today. On August 6 and 9, they flew into history and infamy.

Runway Able, where the A-bomb laden Enola Gay took off. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.

“We stand on Runway Able,” Farrell says as he drives me along the weather-beaten strip of tarmac where history was made in two separate mornings in August 1945.

“This was the exact runway used by both the Enola Gay and Bockscar, the B-29 bombers that delivered atomic bombs to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

This airfield, sun-scorched and silent now, was an expansion of the original Japanese runway, Farrell says. “It was only 4,500 feet long at first. The Americans extended it after capturing the island, paving the way, literally, for the most consequential missions of the Second World War.”

He gestures across the field. “Back in ’45, there was no jungle, no overgrowth. You could see for miles. B-29s parked everywhere.” Now, it’s quiet. Ghostly. The concrete is cracked, but unchanged. Has it ever been refurbished? I ask.

“Never,” he says. “What you see is exactly as it was. No restoration. Just time.”

The old Japanese headquarters in Tinian, close to the runway that would be used by the U.S. to drop atomic bombs on Japan. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.

Nearby lies the former Japanese headquarters, once a center of command. After this are the atomic pits, the holes in the grounds from which U.S.troops loaded the bombs into the B29s in August 1945.

Not long ago, wild cows would wander through the island freely. At one point, the locals were so fed up with the animals falling into the structure’s open pits that they simply filled them in with dirt and planted coconut trees.

Farrell points across the field. “After loading the atomic bomb (Little Boy), they rolled the plane up here.” He points to a precise stretch of concrete. “Right there is where Deak Parsons got into the bomb bay, did a final check, made sure he had the tools to arm the bomb mid-flight. He did it all right there.”

The pit on Tinian, where atomic bombs were loaded into the B29s that would drop them on Japan. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.

During the 60th anniversary of the mission, Farrell met Paul Tibbets, the Enola Gay’s pilot, whose mother’s name was painted just minutes before the flight on the side of the B29.

“I cornered him in Tinian, got him in my car,” he recalls with a laugh. “I wanted to know, from him, exactly what was going through his mind that morning.”

Tibbets had told Farrell this: “I knew we needed every inch of that runway.” He pulled the Enola Gay as far back as possible, turned it around, and positioned it for takeoff.

“The crew didn’t know the true nature of the bomb until after they were airborne,” Farrell adds.

After Japan’s surrender, Tinian passed from the Japanese Empire to U.S. trusteeship, its strategic relevance fading as Cold War tensions shifted elsewhere. The surviving Chamorro population, long scattered by colonial movements, returned from Guam. The Japanese and Okinawan settlers – those who had survived – were repatriated or buried in unmarked graves in Saipan.

Much of the island remained under U.S. lease, with military exercises continuing sporadically. But the wartime peak faded. By the 1980s, the population hovered around 3,000.

“We had cows, fishing, some tourists who came to see the bomb pits,” says Lily, who runs a popular café on the southern part of the island. “Not much, but it was enough.”

Then came the big gamble.

In 1998, Tinian rolled the dice on a new future: high-stakes gambling. The Tinian Dynasty Hotel and Casino opened, a glittering 5-star resort built with Hong Kong money. Ferries from Saipan buzzed across the channel, and locals dreamed of direct flights from China that would have made the paradise extremely profitable.

An undated promotional image of the Tinian Dynasty Hotel and Casino.

But the numbers never added up. Ferry losses hit $1 million a year. Occupancy rates at the Dynasty never went beyond 45 percent, far below the 70-80 percent needed for profitability. And in 2015, the U.S. government came knocking; they fined the casino $75 million for failing to report thousands of suspicious cash transactions. The Dynasty crumbled.

“It was a mirage,” says John, a former casino driver I meet at the small airport on the way back to Saipan. “We thought we were Macau. But when it was decided that the international airport was not to be completed, we all knew would be over soon.”

Today, Tinian has a population of barely 2,000. In the early 2000s it was a trendy destination for families and group tours from Japan but now tourism is in freefall. Visitor arrivals to the Marianas were down 27 percent in March 2025 compared to the year before. The old attractions still exist: the rusting bomb pits, the mile-long runways, the eerie stillness of abandoned Japanese bunkers and shrines. But they draw only a trickle of history enthusiasts and military nerds.

Forgotten it seems – but perhaps not yet entirely.

In 2025, amid rising China-U.S. tensions, the Pentagon is back. With a $409 million investment, the U.S. military has begun reclaiming North Field, bulldozing jungle and restoring World War II-era infrastructure. Over 20 million square feet of land is being cleared.

Somewhere beneath this soil lie the forgotten bones of laborers, soldiers, settlers, and civilians from Tinian’s earlier age.

The remnants of a pre-war Japanese village shrine on Tianian. Photo by Cristian Martini Grimaldi.