As Emmanuel Macron wrapped up his visits to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Singapore – where he delivered the keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue at the end of May – the French president reaffirmed the Indo-Pacific’s strategic importance for both France and Europe. In a context of growing geopolitical uncertainty and renewed unilateralism, Macron emphasized France’s commitment to a stable, multipolar order grounded in international law, freedom of navigation, and inclusive multilateralism – an international posture shared with key partners such as India, Japan, and ASEAN.

Building on this common strategic vision, and as the only remaining European Union (EU) member state with sovereign territories in the Indo-Pacific, France seeks to position its diplomacy not only as a national actor but also as a standard-bearer for European engagement in the region.

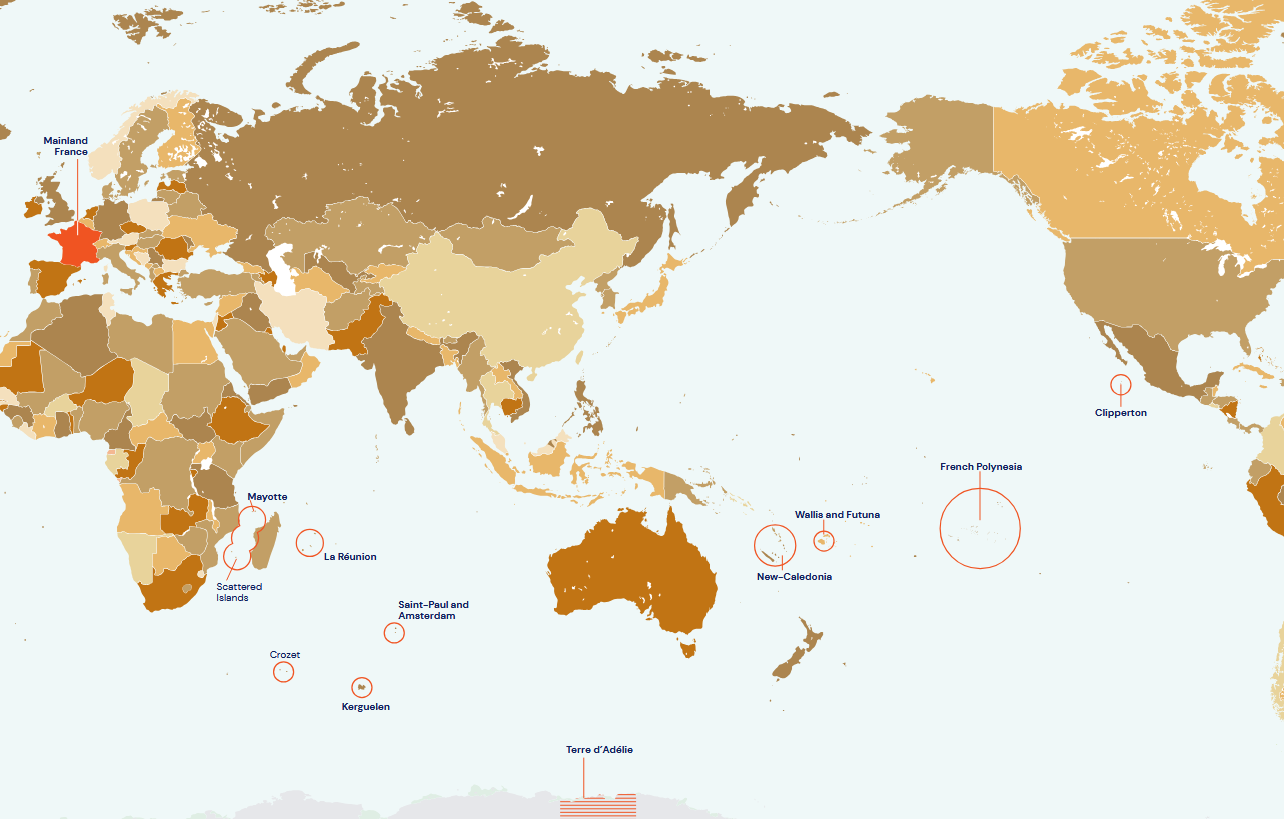

The exercise of sovereignty is precisely what underpins France’s specificity and credibility as a resident power. The French Indo-Pacific overseas collectivities (FIPOCs) – La Réunion, Mayotte, les TAAF (or South Antarctic Lands), New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna, French Polynesia, and Clipperton – which together have a population of 1.65 million inhabitants, play a central role in the construction and elaboration of a credible strategy.

Notably, 93 percent of France’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) lies in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, making it the second largest EEZ in the world after that of the United States. There are also around 200,000 French expats residing in countries of the region, more than 7,000 French subsidiary companies operating in the region, and 8,000 military personnel stationed permanently.

The assimilation of the FIPOCs into a single geostrategic Indo-Pacific framework is a logical step for a state seeking to assert itself as a legitimate actor in the region. However, despite some common geographical, economic, and political characteristics, grouping the FIPOCs into a single macro-region does not fully reflect the diversity of contexts and geopolitical challenges specific to each territory.

A comprehensive and nuanced understanding of local contexts is thus essential to fully comprehend the complexity of France’s Indo-Pacific engagement. This series will explore each of the FIPOCs separately to understand their characteristics, role in France’s Indo-Pacific strategy, and potential friction points between national and local drivers. You can view the full series here; today, we focus on Clipperton Island.

A map highlighting the French Indo-Pacific overseas collectivities (FIPOCs). Map by Paco Milhiet.

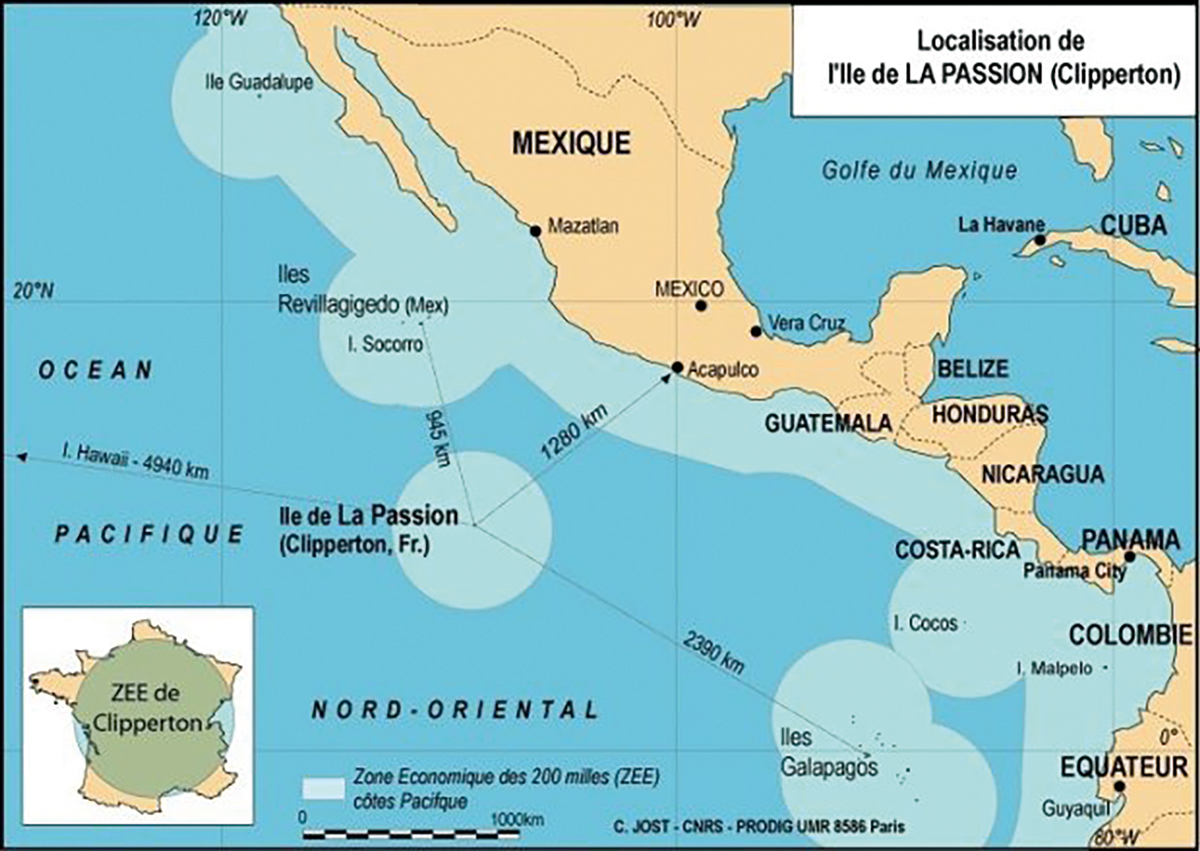

The final feature in our series on FIPOCs is perhaps the least known to the public: Clipperton Island. This uninhabited coral atoll, circular in shape and spanning just 8.9 square kilometers, lies over 1,000 kilometers off the Mexican coast and approximately 5,400 kilometers northeast of Tahiti, in French Polynesia. Although its land area is modest – only 1.7 square kilometers – Clipperton’s strategic and ecological significance is anything but small.

A Tumultuous History

Reportedly discovered in 1706 by British privateer John Clipperton, the atoll was later explored in 1711 by French navigator Michel-Joseph Dubocage, who named it Île de la Passion. In 1858, France officially annexed the territory in the name of Napoleon III.

Throughout the 19th century, Clipperton’s phosphate deposits were exploited by British and American companies. In 1897, Mexico asserted its claim to the island, establishing a small garrison that was later abandoned during World War I. After a series of sordid events, only three women and seven children remained, eventually repatriated in 1917. Since then, the atoll has remained uninhabited.

In 1931, an international arbitration tribunal reaffirmed French sovereignty. Nevertheless, the island was temporarily occupied by the United States during World War II.

A Micro-Territory With Macro Potential

Located at 10°18’ North and 109°13’ West, Clipperton’s geographical isolation and equatorial proximity offer a unique vantage point for scientific observation, including satellite tracking and space surveillance. It is also a valuable site for marine biology, providing critical insight into coral ecosystems, migratory fish patterns – particularly tuna – and climate phenomena such as El Niño.

The atoll is a significant ornithological refuge, hosting tens of thousands of nesting seabirds. Marine biodiversity is equally rich. However, the lack of a permanent presence has left its waters vulnerable to unregulated fishing by foreign fleets, beyond the reach of French enforcement.

Despite its small size, Clipperton offers France the possibility of controlling and exploiting an EEZ of 435,331 square kilometers – larger than mainland France’s EEZ. This maritime domain holds vast mineral, biological, and energy resources. Studies have identified the presence of polymetallic nodules, on the ocean floor, further increasing the strategic interest in the area.

However, this potential rests on a fragile legal foundation. Under international law, the classification of Clipperton as either an island or a rock is critical. According to Article 121(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), rocks that cannot support human habitation or economic life are not entitled to an EEZ. A 2016 ruling by the Hague tribunal supports a broad interpretation of this clause, potentially undermining France’s EEZ claim around Clipperton (and by extension many inhabited islands in French Polynesia).

A Case for Permanent Presence

Despite its potential, Clipperton today presents a bleak reality. The atoll is plagued by illegal fishing, widespread pollution – including military debris and plastics – rat infestation, and even suspected use as a transit hub for Mexican drug traffickers. These issues highlight the urgency of restoring a sustained political authority.

Some observers have even expressed concern that Clipperton could become subject to strategic attention from the Trump administration, especially given recent signs of U.S. expansionist rhetoric.

To prevent such challenges, scholars and policymakers – most notably university professors Christian Jost and Anthony Tchékémian, along with Senator Philippe Folliot – have advocated for the creation of a permanent scientific mission on Clipperton

Establishing a permanent scientific and logistical base would not only reinforce France’s sovereignty but also serve as a platform for ecological monitoring, ocean governance, and international cooperation in the Indo-Pacific – a region of growing strategic importance. Such a platform would both support research and meet the legal criteria established by the Hague Tribunal for effective occupation and governance. Comparable installations already exist in the TAAF where logistical support is provided by the French military and civilian agencies with extensive experience in sustaining remote outposts.

Series Conclusion

The FIPOCs are an important component of France’s international relations in the 21st century. The articulation of a national Indo-Pacific strategy in recent years stands as a testament to France’s sustained engagement in the region. However, this strategic vision often reflects a top-down approach, shaped primarily by national imperatives and geopolitical ambition, occasionally at the expense of local contextualization. FIPOCs tend to be considered less for their internal specificities than for the strategic advantages they offer.

Each subregion – whether the Indian Ocean territories, Polynesia, Melanesia, or even Clipperton – presents distinct geopolitical configurations that challenge an Indo-Pacific-fits-all approach. As France reaffirms its presence and ambitions in the Indo-Pacific, the development of dedicated expertise on these territories becomes essential. This calls for the strengthening of institutions, academic centers, and policy-oriented think tanks capable of informing nuanced and region-specific strategies. Only through such differentiated and well-informed engagement can France fully leverage the strategic potential of its overseas territories while responding to the aspirations of the populations who inhabit them.