Typically, whenever it finds itself facing an adverse international environment, China will look to shore up ties with partner countries as well as its neighbors. So it should come as no surprise to see Beijing acting to strengthening its relations with Russia and Iran, while at the same time putting on the Central Conference on Work Related to Neighboring Countries in April, in a clear statement of just how much importance China attaches to relations with its neighbors.

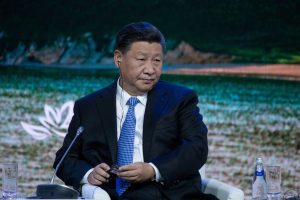

Shortly after the conference, Xi Jinping traveled to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia, accompanied by his daughter, to call for unity within the “Asian family.” In arranging the trip, Beijing was clearly choosing countries also facing high tariffs from the United States. For now, Xi’s visits do not appear to have produced any immediate major results, but the visits may have served as a catalyst for the regional policies that followed.

It is also clear that the visit to Malaysia was a steppingstone for another meeting in May 2025. Premier Li Qiang visited in May 2025, meeting with the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), BRICS, and other groupings meanwhile continue to expand. In this respect, China seems to be getting the help of Malaysia, which emphasizes cooperation with Islamic countries in the Gulf, in creating “minilateral institutions” within broader cooperative associations such as the SCO and BRICS, creating a multilayered organization. Moreover, as is clear from the ASEAN and Gulf countries, this framework is mindful of the Indo-Pacific concept touted by the United States, Japan, and Australia.

Of course, China is not urging these countries to distance themselves from the United States, and as Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has stated, ASEAN countries are not expected to choose between the United States and China. Nonetheless, it is clear that Beijing is keen to strengthen its ties with developing countries and others at a time when the United States is suspending a majority of USAID projects.

In June, President Xi Jinping visited Kazakhstan and led a summit meeting with the leaders of five Central Asian countries. Central Asia does not have a robust framework for convening meetings of its leaders, and this was just the second time that China had organized a summit. The expectation is that this framework will be used on a regular basis going forward. From the perspective of the Central Asian countries, China’s presence is also important in balancing the threat from Russia. Indeed, Beijing is bolstering its economic and social relations with Central Asian countries; the region is already a key transportation conduit from China through Eurasia. In addition to natural gas and crude oil pipelines, a freight railway between China and Iran opened in June 2025, just before the Israeli and U.S. strikes. China is the largest buyer of Iranian oil, and the opening of the freight railway between China and Iran should put the significance of economic blockades and other sanctions on Iran to the test.

As noted, China’s regional strategy is likely designed to counter the Indo-Pacific initiative, while at the same time serving as a means of bolstering relations with neighboring countries in response to the Trump administration. However, Beijing’s actions cannot be considered solely in the context of the United States. For one thing, while China is developing relations with the ASEAN, the Gulf states, Central Asia, and other regions, South Asia is notably missing from the equation. Right now, China is unable to hold a summit with South Asian countries because of the tensions between India and Pakistan and China’s own close relationship with Pakistan.

Yet this is not the only issue. From Beijing’s standpoint, there is also India’s failure to invite China to the Global South Summit as well as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to announce the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) with U.S. President Joe Biden on the occasion of the G-20 summit in 2023. There is also the fact that India and the EU have been working toward a free trade agreement, not to mention Modi’s own active diplomacy, including visits to Cyprus and the Balkans, in recent months. All this means that while Beijing is under pressure to keep the West in check in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere, it is at the same time competing with India.

To better stand up to the West, China is seeking to position itself as the leader of the Global South. Unfortunately for China, however, it is not the only Asian giant with that goal.