Earlier this month, Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim sat across from Mary Ann Jolley, one of the region’s most incisive, unrelenting political interviewers. Known for confronting corrupt leaders with hard truths and questioning them with surgical precision, Jolley has made a name for herself by cutting through spin. Yet, Anwar proved a more elusive target than most. He was affable, measured, and fluent in the language of reform. But beneath the cordiality, two universes collided.

Jolley pressed Anwar on a series of thorny issues: Why was Nuon Thoeun, a Cambodian domestic worker, deported from Malaysia after she posted criticism of then-Prime Minister Hun Sen online? What is Malaysia doing about the Cambodian government’s entanglement in a transnational cybercrime industry that has trafficked and exploited hundreds of thousands and scammed tens of billions of dollars from victims around the world? Why has Malaysia failed to hold powerful players accountable in the 1MDB scandal, one of the most egregious corruption rackets in modern history?

In each case, Anwar deferred – politely, but unmistakably – to the primacy of the state. On Nuon Thoeun’s deportation, he voiced deference to Cambodian sovereignty; the government revoked her passport and his hands were tied. On cybercrime, he praised the “exceptional cooperation” from Phnom Penh – despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. On 1MDB, he warned that further prosecutions could undermine state stability, implicitly reframing justice not as the telos of the state, but as a potential threat to it.

Two distinct moral logics were clearly in conflict here. Jolley posed her questions from the standpoint of a global norms-based international order – one guided by supposed shared standards of rights, justice, and accountability and presumably enforceable by impartial international law. Anwar responded with a logic rooted in sovereignty: that states, and only states, are the ultimate arbiters of legitimacy and action within their own borders. His argument, while disquieting to those steeped in the language of international justice and human rights, is internally consistent and increasingly dominant.

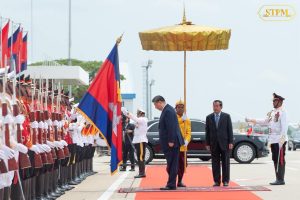

A portion of that same interview reappeared in Jolley’s latest 101 East documentary, which focuses on the Cambodian regime’s brazen and escalating campaign of transnational repression. The film spotlights two particularly chilling cases: the daylight assassination in January of Lim Kimya, a French-Cambodian opposition figure gunned down in Bangkok in what bears all the markings of a government-ordered hit; and the hunting of opposition member Phan Phanna and his family, UNHCR-registered refugees in Thailand, in advance of Hun Manet’s state visit in February 2024. Both episodes reveal the frightening ease with which Cambodian authorities can now project coercive power abroad – and the willingness of neighboring governments to enable it in the name of regional diplomacy or “non-interference.”

For decades, the international order was based on norms that, however inconsistently applied, held that state sovereignty was constrained by certain universal principles: the right not to be tortured, enslaved, disappeared, or defrauded. But today, those principles are increasingly subordinated to the inviolability of the state. Anwar’s tone may have been conciliatory, but the structure of his argument was clear: the state is supreme, even when it is unjust.

This turn is not unique to Southeast Asia. Across the globe, states are asserting sovereign prerogatives with renewed confidence – often in direct defiance of international norms. Russia justifies invasion under the guise of historical entitlement. China cites non-interference while silencing dissent across borders. And the United States? Once a flawed but vocal advocate of rights-based leadership, the U.S. is, for better or worse, now fully retrenched and defocused from such battles.

And to be clear: as this international order crumbles, it is not merely because of the rise of autocrats or the retreat of democrats. It is not merely a cynical authoritarian innovation. It is also, in part, a response to the cynical use of norms by those who claim to defend them. Too often, human rights have been instrumentalized – used to justify wars, punish adversaries, or selectively name-and-shame, while allies commit abuses with impunity. This hypocrisy has not gone unnoticed. It has undermined the legitimacy of the entire enterprise and empowered a generation of leaders who now meet calls for justice not with denial, but with a more strategic – and in some ways more effective – response: “We do not recognize your jurisdiction.”

In other words, for many states, especially in the Global South, sovereignty is not merely legal cover for state predations; it is also a moral narrative that supports national identities forged, in many cases, in struggles against Western colonial rule. It signifies independence, self-determination, and dignity in a world that has too often denied them those things. And unlike the aspirational human rights regime, this moral frame offers a kind of internal consistency: what happens inside a country’s borders is that country’s business.

But herein lies the danger. In today’s world, the claim of sovereignty is just as likely to shield organized repression and kleptocracy as it is to protect national independence. From Cambodia to Russia to El Salvador, sovereignty is now deployed not just (or even primarily) to resist Western interference, but to suppress dissent, protect elites, and dismantle accountability. In these contexts as elsewhere, sovereignty has ceased to function as an instrument of justice at all. Instead, it is, more often than not, simply the arena in which power consolidates and perpetuates itself.

And so the state, once imagined (yes, by a norms-based international order) as the guardian of rights and the executor of justice, now operates with few moral or external constraints. Instead, it has become both the sword and shield of autocratic coercion and elite excess.

In Southeast Asia at least, Cambodia is perhaps the clearest example. Under the supposedly “reform-minded” Hun Manet, the regime has only accelerated its descent into criminalized autocracy. The forced scamming industry alone – a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, built on slavery and exploitation – is protected by Cambodian police, legitimized by Cambodian government propaganda, and defended by Cambodian officials in international forums as a matter of “internal affairs.” And the Cambodian reality neither begins nor ends with its scam economy – the Kingdom’s resources are being plundered, its workers exploited, its dissidents hunted abroad. Elite impunity is the law of the land.

And yet, the international community largely nods along. Aid continues to flow. Investment resumes. United Nations agencies kowtow. Photo-ops are staged. For a regime whose abuses are increasingly global in scope, the rewards of sovereignty remain plentiful, and the costs negligible.

Yet there are no easy answers to the modern mafia state: neither sovereignty nor the current international system is equipped to confront the scale of today’s crises, or the deftness of its most malign actors. In a world of metastasizing injustice – climate collapse, systemic corruption, forced displacement, digital exploitation – neither model speaks with sufficient credibility or urgency to the scale of human suffering.

That does not mean the struggle for rights is obsolete. But it does demand strategic reorientation. It is no longer enough to issue statements or appeal to values that are not widely shared. Rights defenders must invest in new centers of moral gravity: localized institutions, grassroots movements, independent investigative networks, and survivor-led initiatives that do not depend on the state’s permission to act.

The future may well belong to the criminalized autocracy: rhetorically agile, economically integrated, and sovereign to a fault. But that is also not the only future imaginable. The state may have failed as an arbiter of justice, but people – organized, informed, and morally resolute – still matter.

And ultimately, a counter-witness begins not in the halls of power, but in the kinds of questions Jolley asked – and in a collective unwillingness to accept their dismissal. This posture of questioning need not reject the state as a unit of organization, nor abandon international institutions altogether. But it must stop treating either as the singular vessel of moral authority. Sovereignty may have won the argument for now. But the deeper struggle remains: to ensure that the rights of individuals and communities are not buried beneath the weight of unchecked power, whether exercised in the name of the nation, or of norms.